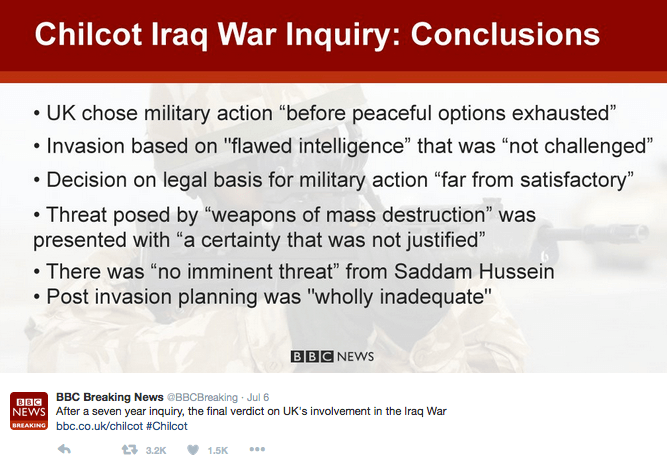

The British Government’s public inquiry into the UK’s role in the Iraq War concluded last week with the publishing of a report by Sir John Chilcot, who chaired the Inquiry. Commentators have labelled the Chilcot Report‘s verdicts as damning, and the documentary evidence gathered has pointed to many flaws in the decision of the Blair government’s (and by association, Australia’s Howard government) decision to join the Iraq invasion.

Sajjeling asked five writers of various Iraqi backgrounds to share their thoughts in response to the Chilcot Report’s conclusions. Here is what they had to say…

***************

An Iraqi child lights a candle at Al-Diwaniya in memory of those who died in the Baghdad Attacks. Image: Hawraa Adnan

23-year-old Fadak Alfayadh is a Melbourne law student. Originally from Iraq, she was born in Baghdad and lived between the capital and Nasiriyah before moving to Australia.

I still remember crouching under the stairwell with my family for hours while the bombs dropped around us. I was only 10-years-old at the time, and I had never heard anything so loud. Everything around us shook; windows broke, and all we could do was pray that we be spared.

Months later, bombs were no longer being dropped over us but Iraq had became unlivable. Along with thousands of other Iraqis, my family and I left everything behind and fled to Jordan overnight.

In the aftermath of the Chilcot Report, some comments have come close to romanticising the pre-invasion Iraq of Saddam Hussein’s time. Earlier this month, Kadhim Sharif Al-Jabouri, the man who had knocked Saddam’s famous Firdos Square statue with a sledgehammer a few weeks into the invasion, told the BBC in a TV interview that he feels “pain and shame” when he sees the toppled statue and wishes he could “rebuild it”.

But living under Saddam’s regime was never a tranquil experience. Many people were killed for simply voicing their political opinions or showing slight opposition – Al-Jabouri’s family members included.

Saddam also dragged Iraqis into a number of international wars and disputes. No surprises there, of course; that is what happens when a psychopath rules a nation.

Having said that, the invasion of Iraq was a huge mistake, in my view, because – as the report suggests – other methods could and should have been exhausted prior to taking military action against a Sovereign State. I am confident that, had the UK and their allies equipped them with the necessary means, Iraqis could very possibly have rid themselves of Saddam. I say this because, on numerous occasions prior to the invasion, there were uprisings, attempted assassinations and attempted revolutions initiated by Iraqis against the regime.

Since the release of the Chilcot Report, the media spotlight has of course been focused on the former Prime Ministers who led the UK and Australia into the war. But the comments from John Howard and Tony Blair in response to the Report’s findings have been highly insulting to every Iraqi; their statements held a lack of demonstrated remorse for what they did to us.

On the one hand, Blair said that the world is now “better and safer” after invading Iraq, leaving me to wonder whether he really lives in the same world as everyone else. Similarly, John Howard, continued to defend his government’s decision to invade Iraq back in 2003, further adding insult and grief to the memory of those murdered.

Hundreds of thousands of Iraqis were killed, and more were forcibly displaced because of this invasion. Blair and Howard’s lack of regret makes me question their humanity and believe them to be more of a cruel threat than Saddam ever was.

I’d like to see Australia initiate its own inquiry to investigate the legitimacy of its involvement in the invasion of Iraq. Australia, under John Howard and his government, contributed to the demolition of Iraq; it too should be held accountable.

30-year-old Ayesha Baba is a Sydney lawyer. Born in Sulaymaniyah, Iraq, she is an Iraqi-Australian of Kurdish ethnicity.

As a solicitor practising in the area of administrative law, reviewing decisions made by administrative agencies of the government, my role requires me to have regard to principles of natural justice and procedural fairness. When arriving at a decision, I am required to give written, transparent reasons based on evidence that would satisfy a reasonable person.

But the findings from the 7-year-long Chilcot inquiry – particularly its assessment that the process of identifying the legal basis for the invasion was “far from satisfactory” – and the information leaked to the public since the invasion, are proof that such practices never took place in the British (and Australian) government’s decision-making in 2003. When I think about the relatively minor decisions that I make in comparison to these governments’ decision to invade a country, I find this assessment to be both baffling and extremely saddening.

Former Australian Prime Minister, John Howard, responded to the findings of the Chilcot report by saying, “I don’t believe that, on the basis of the information that was available to me, it was the wrong decision. I really don’t.”

This justification was described by another former Australian Prime Minister, Paul Keating, as a “stubborn and unctuous denial” that should be “held in contempt by every thinking Australian”.

Having been welcomed to Australia as a refugee with my family in 1993 by the Keating government, and having witnessed the change in Australia over the years from a harmonious multicultural society to one where our empathy and compassion appears to be reducing each year, Keating’s response to Howard’s failure still to provide proper reasons resonates.

When asked about my background, many people respond with a comment along the lines of, “Oh good, the Kurdish areas [in Iraq] are not affected”. While this may be true to some extent, hundreds of thousands of innocent Iraqi civilians have been killed. The US justified the invasion by framing it as a war that would bring the.gif"4265" class="alignnone size-full wp-image-4265" src="https://sajjeling.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/screen-shot-2016-07-11-at-12-15-18-am.png" alt="BBC tweet" />

26-year-old Hawraa Adnan is an Arts graduate from Perth. She is of mixed Iraqi heritage, with a Kurdish grandfather and an Arab grandmother hailing from Sulaymaniyah and Diwaniya respectively.

“I feel like I’ve been picked up from my normal life yesterday and placed in this new one today. I never get used to this,” Murtada Marzog tells me. An Iraqi immigrant, he was forced to flee Baghdad a decade ago.

As Iraqi exiles, the news of Saddam’s fall brought me and my family great joy. It meant that we would finally be able to return to Iraq; and that we did. We packed our bags and headed off to meet our family in 2004 for the first time in 14 years.

There was no easy way to get to Dora, Baghdad, where my extended family had settled. We took a plane to Dubai, a ship to Basra, and then endured an eight-hour drive to the capital. Those first three months in Dora were the happiest of my life, making so many new friends with the cousins I never knew, going out in packed cars to Karada for late night ice cream and feeling like a real teenager for the first time.

As an Iraqi kid who experienced trauma in my childhood, I had never felt like a normal child. I always felt older, and at 15-years-old I felt 40. I was vaguely aware of the jailing of the men in my family, including my dad who was jailed for seven years. I only later learned that not all who were taken away were actually jailed; many were executed on the same day that they were taken. This information only became available 14 years later, when the invasion opened up the jails and their records to the Iraqi public. Many of our missing family were declared dead, and I witnessed my family go through unbearable Post-traumatic stress disorder in full swing – particularly my cousins whose fathers, unlike mine, never returned.

After returning to Australia, we kept hearing about the rising violence in Dora; first came the church massacre, and then the systematic targeting of Shias. Finally, our family in Iraq fled to Al-Naseej, a city about two hours south, and Dora was officially segregated with giant concrete slabs, just like many other districts before it.

What started off as a perceived blessing turned out to be a horrific curse.

Iraq is treated like game of monopoly by the world, and the Chilcot Report proved to me that we can’t expect any support from the same people who.gif"caption" id="attachment_4378" style="width: 2122px" class="wp-caption alignnone">

Sydney’s Iraqi community rallied on Sunday in solidarity with their friends and family in Iraq. Image: Sarah Yahya.