By Amal Awad

There is no denying that Arab cinema is emerging on the international scene as a dynamic industry that deals in real life with both comedic flair and gritty reality. Even directors with hardened perspectives like Palestine’s Hany Abu Assad, who depicts the grim truth of life under occupation in several films (Paradise Now, The Idol and Oscar contender Omar), offer doses of comedy in the films to balance out the drama.

In fact, Arab filmmakers are to be commended for their refusal to indulge Western curiosity and judgment of late. It would be easy to address a global audience by playing to their fears of terrorism and strife in the Arab world, particularly amongst Muslims. But Arab filmmakers today are more interested in exploring their own curiosities.

The result is that we are treated to an impressive slate of films that, not unlike some of the most memorable films to come out of Europe, the US and the UK, are interested solely in exploring the complexity of human experience from that culture’s perspective.

Suha Arraf questioned the value in holding onto the past in her profoundly beautiful film Villa Touma; Nadine Labaki rebuked and mocked fundamentalists of all creeds in Where To Now?; and in last year’s From A to B, Ali F Mostafa invoked the classic Hollywood road movie for “bros” and turned it on its head by touching on the tragic imbalances of the Arab world, pitting those who have physical riches but no inner peace against those who lack both.

Suha Arraf questioned the value in holding onto the past in her profoundly beautiful film Villa Touma; Nadine Labaki rebuked and mocked fundamentalists of all creeds in Where To Now?; and in last year’s From A to B, Ali F Mostafa invoked the classic Hollywood road movie for “bros” and turned it on its head by touching on the tragic imbalances of the Arab world, pitting those who have physical riches but no inner peace against those who lack both.

And who can forget Labaki’s teasing silhouette in Caramel ? That film is nearly a decade old, but left no one out – the Muslim woman who is about to be wed but is not a virgin; the young woman dealing with her sexuality; the older woman who is grappling with her age; and, of course, the beautiful one who, despite all she has going for her, succumbs to the temptations of an affair with a man who has no intention of marrying her. The tagline may well have said in block letters: ARABS ARE JUST LIKE EVERYONE ELSE. Instead, she took well-used tropes and gave them a distinctly Lebanese flavour.

And while much of the above could, you might think, be easily applied to a Western setting, these Arab filmmakers are not painting by number. Even when, at the core of these films, there lies a quest for inner peace and personal freedom, it suggests a depth that American cinema, for example, lacks. The tragedy of the West is addiction and heartbreak; the downfall of Arab society is its obsession with appearance and fate.

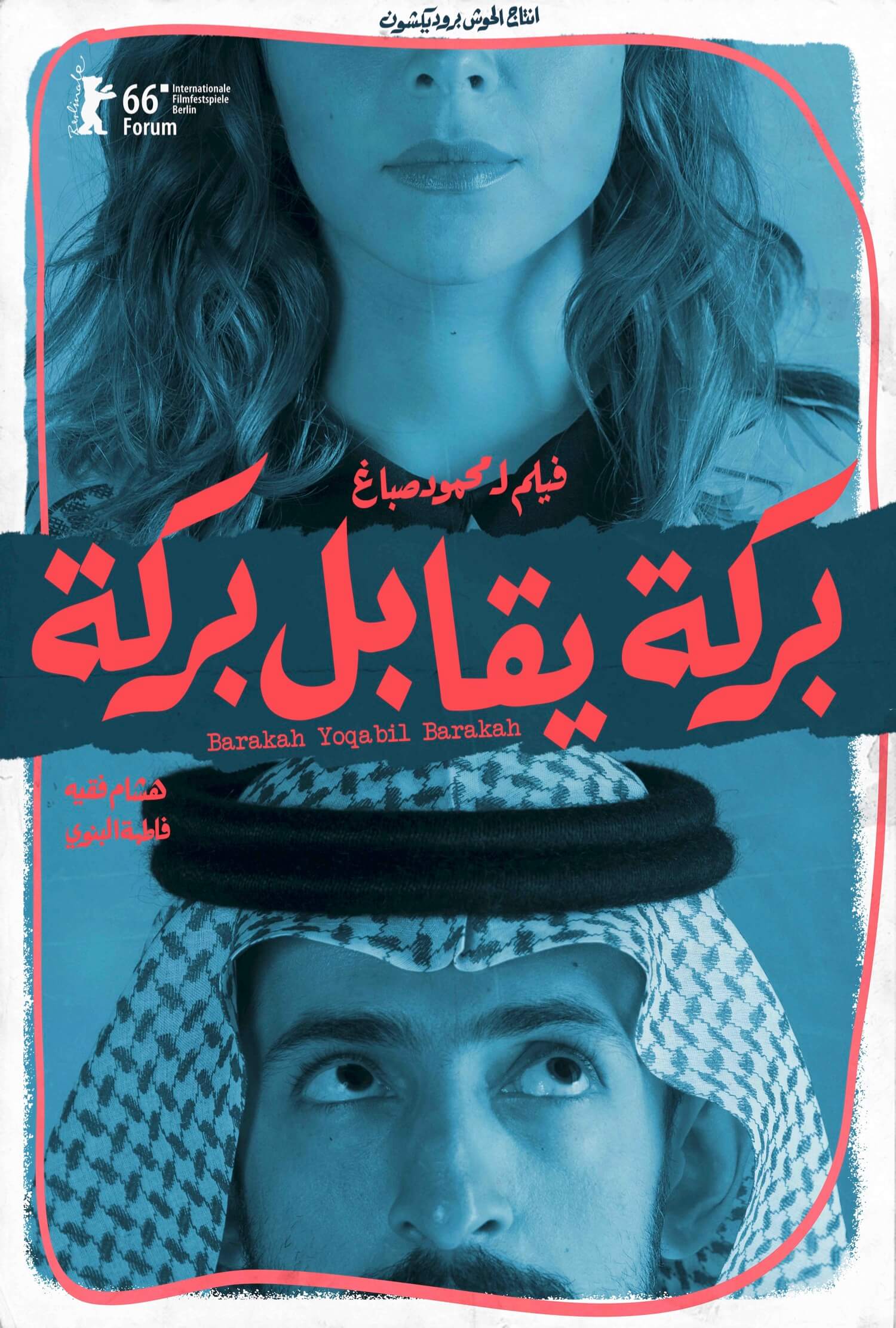

It’s something that struck me deeply as I watched a new romantic comedy that has come out of Saudi Arabia and is screening at the Sydney Film Festival this week. At the helm (as both writer and director) is Mahmoud Sabbagh, who is very pointed in the fact that he has made a comedy. He told Al Jazeera that no one wants to see a film about Saudi Arabia’s restricted public life, and so he disguised it beneath a romantic comedy.

It’s understandable; what could be more universal than romance? What can be more accessible than comedy?

It’s a truth universally acknowledged that first dates can be super awkward. Image supplied.

Barakah Meets Barakah tells the story of a municipal worker in Saudi Arabia, Barakah (Hisham Fageeh), who lives a quiet life in a “ghetto” neighbourhood, tending to the needs of his neighbours, who in the tradition of romantic comedies, don’t command a major storyline but play amusing, larger-than-life characters.

In his work, Barakah is a fair-minded, kind disciplinarian – he hates fining people, but he holds on to some core beliefs. His job, in all areas of his life, is to clean up other people’s messes – in between rehearsals for a local theatre performance of Hamlet, in which Barakah’s co-worker, a tragic creative Maqbool (Abdulmajeed Al-Ruhaidi), has shepherded him into the role of Ophelia. It’s Saudi Arabia, after all, so no women allowed. This could have flat-lined as a sub-plot, but it worked. The silliness of staging Shakespeare performed purely by male “actors” in the same way it would have been done in Shakespeare’s times delivers some comical moments.

The film takes time to warm up, but eventually Barakah meets Bibi ‘Barakah’ Harith (Fatima Al-Banawi), an Instagram celebrity who seems perpetually dissatisfied even as she rakes in the big bucks for her “brand”.

Your standard American rom-com is a game of “will they or won’t they?” or “what happens now that they’ve slept together?”. Sabbagh’s more sanitised version is far simpler: how do you even go on a first date when every scenario in public promises the threat of being raided by the Religious Police?

There are moments of pure criticism, but Sabbagh manages this with poignancy and an even hand. He is asking, quite simply, how his society got here. Here, where everything is forbidden, and individuality is an offence. He gets away with it because he’s Saudi, and it’s his issue to query.

“Saudi Arabia, like any other society that is in a transitional mode, has both sides. And it’s our role as local filmmakers to bring these stories out to the world,” Sabbagh says.

“In the film, I wanted to show a brighter image of Saudi Arabia and its people. Apart from the depiction of repression in the country.”

“In the film, I wanted to show a brighter image of Saudi Arabia and its people. Apart from the depiction of repression in the country.”

Really, what Sabbagh is doing is “normalising”. His story is not so much a plea for acceptance as a statement of fact.

“Saudi Arabia is among under-represented countries in the world in terms of storytelling, and I want to make more storytelling about what life is like here. Not propaganda, of course – the film is very candid, very honest. But there is a lot of demonising in the press in the West about Saudi Arabia, and I think this film will be a welcome relief that humanises the country,” he says.

For many, the film will be a statement on the sorts of issues that plague many societies: class and wealth; opportunity; beauty; freedom. But it’s clear quite early in the film that Sabbagh is working within his own imagination and his society’s contextual confines. A noticeable example is Sabbagh’s choice of intentional censorship – done for effect, not for compliance. When Bibi has a henna tattoo painted on to her belly, we see it being done but her belly is pixelated. When a character pours a glass of alcohol, the glass too is pixelated. When the characters move in for their first touch, Sabbagh cleverly hides them in silhouette behind a white sheet.

“These are the images we grew up seeing when watching films, so I wanted to put some into the film to emphasize how illogical it is,” he says.

Whether Sabbagh is making a point or adhering to strict guidelines, his overall point is clear – that life in Saudi Arabia is tightly regulated, and the only freedom one can find, truly, is within themselves. Even Bibi’s celebrity does little to shake this idea of repression; she makes money for just checking in to an event, but only takes photos that show half her face, and she is verbal in expressing her dissatisfaction about the “fakeness and hypocrisy” of life in the kingdom.

“You enjoyed your youth then didn’t defend our right to the same privileges. I blame your generation,” scolds a newly-awakened Barakah (the guy not the girl) to his silent, disabled father. It is his flowering interest in Bibi that has begun to affect him, but Sabbagh suggests this is not so much a change as an inevitable unfurling of authenticity.

Who doesn’t want love in their life? Who doesn’t want a life of meaning? Who doesn’t want to have control of how they live?

This is lead actors Fatima Al Banawi and Hisham Fageeh’s feature film debut Image: Supplied.

Arabs in the west are often straddlers; one foot in the country of their residence and one in the homeland. It can be confusing, painful even. But we are afforded the.gif"text-align:justify;">Oppression is a heavy word, and it’s at the heart of this film. Even as Sabbagh wants to suggest that freedom comes from within, you’re left with the sense that his dream of a more liberal, creative society is weightier than his hope that it will happen soon.

In fact, he moves from an unblinking and sensitive portrayal of Saudi society – a blameless, neutral acceptance of its restrictions – to a critical attack on the futility of life under regulation.

Still, it’s not meant as an appeasement of western sensibilities. The concern here is not how Arabs stack up next to westerners; it’s that they lack choice to decide for themselves. This is not a world viewed myopically from the point of view of someone who sees the west as best, and this is what makes it refreshing.

Wadjda was the first feature film shot entirely in Saudi Arabia.

This is not the first notable film to come out of Saudi Arabia. Keif Al-Haal, a far darker foray into Saudi life, addressed many of Sabbagh’s subjects: class, love in a strict society and the place of women.

And there was the international film festival darling Wadjda, a very sweet tale about a girl’s quest for a bicycle in a land that forbids her to ride one, which drew attention particularly for its female director, Haifaa Al-Mansour. It was commended not only for the skillful storytelling (a very Hollywood-inspired, or arguably, Iranian-inspired, tale), but for the fact that a woman(!) from Saudi Arabia was behind it.

Let’s move beyond the obvious stuff here: a female filmmaker from a country that is famous for ordering its women to veil. Yes, she shattered perceptions of her country. Yet .. yet… her film depicts a life of rigidity, and one in which the result of not being able to deliver another child leads to a polygamous marriage.

This film too deals with the male obsession with having multiple wives. Sabbagh may use comedy to distill it, but his criticism of a society that is unfairly skewed towards male privilege is unmistakable.

And this is what is surprising and remarkable about Barakah Meets Barakah. It’s well-written for the most part and it’s funny, but it’s also heart-wrenching because you know that Sabbagh is holding his tongue. He wants to say more. He wants to be more explicit. Yet even amid the self-censorship he tells you, in no uncertain terms, that all humans struggle for freedom, and that pain is universal.

Barakah Meets Barakah premieres at the Sydney Film Festival tonight and screens again on Friday 17 June 2016 at 2.20pm in the State Theatre. Tickets can be bought online.

__________________

By Amal Awad

Amal is a Sydney-based writer and author of three books. Last year she followed up her debut novel, Courting Samira, with the sequel, This Is How You Get Better, and she has also published a collection of columns and essays entitled The Incidental Muslim.