Ghourbah, an Arabic word, does not have a direct translation into English but it stems from the word ‘stranger’. It refers to a feeling when one has unwillingly left their home and community to move to a place where they do not belong. Ghourbah is the constant feeling of longing, loneliness and inability to belong.

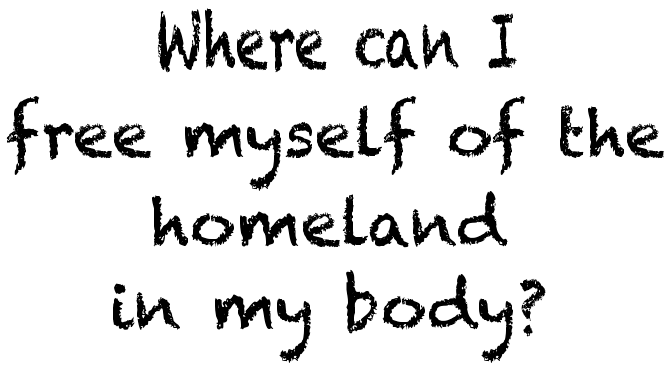

A quote by Mahmoud Darwish in his anthology, “Unfortunately, It Was Paradise: Selected Poems”

When you take on a lover, you envisage them to be a certain way. But, that expectation, in most cases, is far removed from reality. This romanticisation extends from people to places; that is, we have a tendency to remember a place in which we once lived as we last saw it – on its best day. The images of streets in the corner of your mind remain untouched. Indeed, for me, the sounds of everyday hustle in the markets and the scent of my grandmother’s freshly baked bread were all ingrained in my memory as I last saw them.

Having spent an equal amount of time of my life in Iraq and Australia, my heart was always in Iraq. Eventually, I came to learn that years of longing were for a place that no longer exists. My Iraq is no longer; it is nothing like I remembered or hoped it would be.

It was late 2014 when I made the trip back to Iraq. I had not been back to Baghdad since we left in 2003, only six months after the American invasion. We had a good life in Iraq, and only left because it became unsafe and unlivable. Despite the effects of war, my recollections of Iraq were all positive.

My biggest fear when returning to Iraq was that I would not feel a sense of belonging. I knew that the country was not in a stable state and it had been 11 years since I had left it, so it must have drastically changed. I had so many great memories and I was afraid that I would have to replace them with images of war and devastation. I worried that if it were not exactly as I’d pictured it, and just as lovely as it was when I was a child, my strong attachment would be shattered.

Unfortunately, I came to realise that the Iraq to which I had long dreamt of returning had been stolen from me.

Baghdad was nothing like I imagined her to be. Within a few hours of landing, I had mixed emotions. Seeing my family after 11 years and hearing my mother tongue spoken everywhere made me cry tears of happiness. People looked like me, they had my skin colour and I almost got away with looking local. For a brief moment, I felt like I had found myself after so many years of struggling with my identity.

Road blocks divide Al Jamhouriya St, Baghdad (2012).

The war, however, and its aftermath, have left their mark and continue to affect the country. My recollections of balmy evening walks with cousins to the park to play on the swings were replaced with visions of large concrete walls cutting the city in half. Sounds of Fairuz in the morning were replaced with sounds of gunfire and bombings in the distance. Checkpoints were ubiquitous reminders of the ever present danger.

I loved being with my family, especially with the cousins with whom I grew up. We remembered old stories and jokes together, played the games we used to play as kids and visited places we used to go to together. However, I couldn’t help but wonder if I seemed foreign to them.

I must’ve been a different person to the girl who fled Baghdad with her family in the middle of a cold November night. I now have a privileged life in a rich country with a stable job, a good education, and easy access to medical care. Most importantly, I don’t share their daily fear of bombings and kidnappings and the effects of a corrupt state on every part of my life.

Street signs, which depict images of important figures in Islam, litter the streets of Baghdad (2012).

I returned to Iraq at a time when ISIS was portrayed to be a big problem in the Western media. Without doubt, IS has affected the lives of hundreds of thousands of Iraqis through displacement, murders and sexual exploitation of young women. On the streets, we saw displaced Iraqis and Syrians scattered with no work or homes. We were worried that IS would extend to Baghdad and have a direct effect on our families.

It was a surreal development. The Iraq in which I grew up held little value for religion, but the Iraq I was re-visiting was engulfed in religious extremism. Non-Shia Muslims had become alienated and ostracised. The walls on almost every street in the city were covered with posters of prominent Shia religious and political figures.

This was mass indoctrination of religious dogma instilled through fear. People who did not want to be religious would be isolated, ostracised and at times receive death threats.

Where my aunt lives, people woke up to posters of Muqtada AlSadr during Muharram. People were too afraid to remove them (AlMahdi Army would attack you if you did), so those posters remained there for months only to be washed away by the rain.

Through governmental structures, new legislation and social changes, Iraq had become more conservative and is presented to the world as well as its citizens as a Shia Arab state. The presence of Iraq’s many cultures and nationalities is leading to its downfall because those in power are using the differences to divide and then subjugate the masses to their will.

It left me utterly bewildered at what my country had become.

When I returned to Australia, my sister asked me, “Did it feel like home?”

I had placed a lot of hope upon returning to Iraq, so much so that it became heart-breaking that I could not say “yes”. Living in Australia for so many years without a sense of belonging had made me long for Iraq. Sometimes I wish that I did not return, and had Iraq remain as my distant mysterious lover.

By Fadak Alfayadh

Fadak is a law student and human rights advocate based in Melbourne. She aspires to work in human rights law and to write about it along the way. Fadak’s work is particularly driven by refugee issues in Australia and around the globe. She also has a passion for Middle Eastern feminism and politics.

I will share with displaced people I write to..some may not like it, as so recently displaced and in camps, they long to return home.

Like Like