A Leb, a Wog and a Bogan transport audiences back to when the Sydney gang rapes took place in the year 2000.

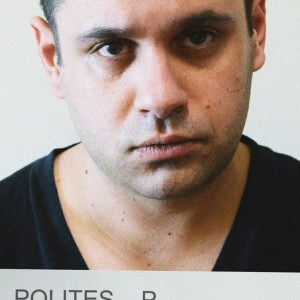

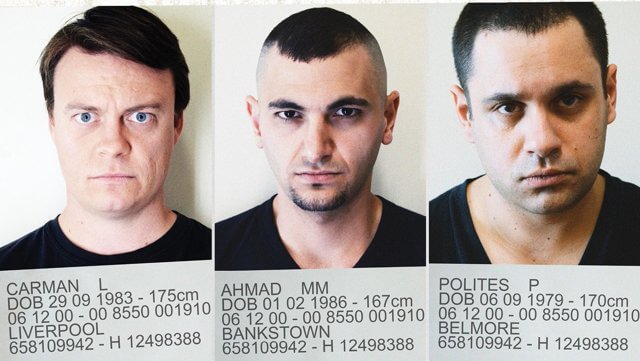

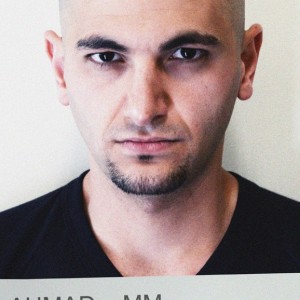

In a performance-reading piece titled #Three Jerks, the lived experiences and anecdotes of Michael Mohammed Ahmad, Peter Polites and Luke Carman, who were schoolboys in Western Sydney at the time of the incident, are weaved together to tell a bold and captivating story.

The show, which premiers this weekend at the Sydney Writers’ Festival, offers audiences a proverbial magnifying glass to examine how the media vilification of Arab-Australian and Muslim men has impacted men of the Westside.

I spoke with #Three Jerks co-creator and performer Michael Mohammed Ahmed about the performance piece, Arab-Australian men, the literacy movement in Sydney’s western suburbs, sexism, racism and more.

Michael Mohammed is the director of Sweatshop, author of The Tribe, and a doctoral candidate at the University of Western Sydney.

******

Why are the three of you jerks?

Why are the three of you jerks?

We’ve called it Three Jerks because we are already positioning ourselves in a controversial position. My sub-line is: we know. We know we’re jerks, we know what we’re saying is offensive, we know that the work is problematic, so now that we’ve admitted it, now that we’ve said we know, don’t judge us. Just come in and listen to what we have to say. It’s really important you take it on board.

Just getting it out of the way.

Yeah, getting it out of the way. We admit it, you know. If you’re going to go write a review about us where the first thing you say is, “These guys are jerks” – don’t waste your time. We’ve said it, we know. That’s an easy position to have imposed on us, as men from the western suburbs of Sydney. You know, we’re seen as jerks anyway in the media, in politics, (and) the police think we’re jerks. We call each other jerks.

…And women think we’re jerks.

What is the story?

Luke’s story looks at a robbery that he and his friends commit that goes wrong. Peter’s story is about the interactions he experienced through the porno bookstore he worked at, his family in Belmore as Greek-Australians, and through the business my family was running. My story is about…

…Actually, can you take that bit out? You’ll see.

Throughout the show there are these news flashes that come up, chunks of writing that look at the media presence at the time of the gang rapes. Comments made by the Mufti, comments made by Bob Carr, what the news reporters were saying and the language they were using. When we talk about the gang rapes, it wasn’t the gang rapes that impacted the young men of Western Sydney. If the media hadn’t mentioned it, we wouldn’t have heard about it. The show is about how the media, the politicians, and the police reacted to it. Because the way the police reacted to it is that they started to target us.

Ah, yes, the Middle Eastern Crime Squad.

Yup, the Middle Eastern Task Force

Even African-Americans say it’s the most racist thing they’ve ever heard of.

It’s frikkin racist.

Of course it’s racist. There’s a black rapper and poet from Tupac’s group, Outlawz, named Napoleon who said it would be like…imagine if one of these Lebanese-Australian gangs just woke up tomorrow and decided to target Anglo-Australians. Wouldn’t you consider that racist? It’s the same thing. Three Jerks is looking at the way all those things affected us.

How do you think the gang rapes have impacted Arab men? And since there’s a Bogan and a Wog involved too, how has it impacted them?

As a Lebanese-Australian Muslim, everything about us, our identity, our culture, our history, our traditions, our appearance, was simplified. It didn’t matter that I was Muslim-Alawite, or that I was educated, or that I was law-abiding, or that I was keeping my virginity until I was married, or whether I had liberal politics, or whether my mum and dad were Liberal, or whether my mum wore a hijab or not – none of that mattered. All of a sudden, we all just became the same thing.

‘Leb’ became a term for all people of Arab-Australian backgrounds….so if you were Palestinian, or Syrian, or Jordanian, if you were from Egypt, or in some cases if you were Turkish, or even Indonesian, you might have been called a Leb just because of your appearance.

Peter Polites, when we say he’s a wog, we mean he is of Greek-Australian background. Peter is of Middle Eastern appearance. For a long time though, Arab-Australians called themselves ‘wogs’ and people would say that we would have looked Mediterranean, like Greeks. But after the gang rapes and 9/11…Greeks started to look like Arabs.

A certain kind of appearance – the Arab-Australian appearance – began to not only become something that affected our lives, but it began to affect the lives of people with a Mediterranean appearance, so Peter, (if you saw him) walking around here, you’d just call him a Leb. All those kinds of stereotypes that were branded on me were branded on Peter – that’s how it affected Peter.

For Luke, it’s very different, because we’re talking about an Anglo-Australian who grew up in the western suburbs of Sydney. Anglo-Australians see themselves as the dominant cultural group in Australia, but not in the western suburbs. They’re a minority here. There were probably three Aussies at the high school I went to – three Anglo boys – and everyone else was Arab-Australian. They were, in their own right, a minority.

Luke grew up in a space where Arab-Australians were the dominant cultural group, and they were being rejected. It was a conflicting situation; this is a group that he, in some ways, knows are not villains, but he also does know that there is villainy within that community. He also sees it from the outside. He’s the Wog. He’s the Leb in that situation. He’s the Other.

And we existed in this world at the same time. Three Jerks is about how men of different backgrounds from Western Sydney reacted to this climate and media onslaught.

Are you interacting with each other directly onstage?

We’re connected to each other, but it’s always at the audience.

It’s the first time I’ve tried to do something where we’ve got writers who are performing on-stage reading three stories that are interconnected. In the past, we’ve done a lot of performance readings with a writer on stage doing a reading one-on-one with the audience. But this is the first time we’ve created a co-authored script between three writers, and we stand together, bound together on stage, reading these three interconnected pieces. So while Peter Polites reads his story, I’m a character in his story, so I come in as a performer, and do lines as myself from my story.

The three of you are performing as part of the Sydney Writers’ Festival this Saturday. What do you want the audience to leave with? Are you trying to challenge them? What is it that you are trying to do?

It’s a good question because we’re not about positive representation. Is it going to challenge people? It’s not going to challenge people in the sense that (they’ll be like), “Oh, you know, I thought Arabs were bad but it turns out they are really good”.

My work is looking at the position of Lebs, Arab-Australian Muslim men, and how our behaviour was impacted by the gang rapes, and also what our behaviour was. Because I think a lot of the behaviour of young Arab-Australian men at that time was pretty misogynistic anyway. We weren’t rapists, but some of the behaviour of the young men I met was problematic, and I think a more complex investigation needed to be under way.

I don’t care about positive stories. Because to be honest, some of my friends were shot and killed in this place where we are sitting, in Bankstown. Kids have been stabbed and shot dead at the train station. A friend of my brother’s, Omar El-Chami Batch, was shot and killed in 2001 at a bus stop in Bankstown by members of a Vietnamese-Australian gang.

The high schools that I went to – Punchbowl boys, and before that I went to Birrong boys – I saw boys get stabbed in the head. Once a month! Those stories need to come out. I don’t think it’s about saying this is all good and dandy. It’s about offering a complex understanding as to why those things happen.

Those things don’t happen because of ethnic tension, those things don’t happen because we’re Arabs or because we’re Greek. It’s about looking at class, race, sexuality, gender…

It’s intersectional, isn’t it?

It’s intersectional, isn’t it?

Yes, it’s about looking at the intersections of these issues. And at the core of it, it is looking at the socioeconomic position of these people. We’re talking about young men going to extremely disadvantaged schools, they come from disadvantaged households, there’s no literacy, there’s no education, and there’s no money.

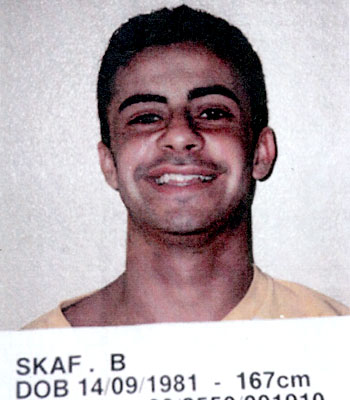

It’s about offering a complex critique, and not just attributing it to someone’s racial issues. There’s a book called Evil in the Suburbs by Cindy Wockner and Michael Porter, who were investigators in the Skaf crime. They talk about – I think it’s on page 21 – how before Bilal Skaf became a big-time criminal, he went to Lebanon, and (it was like) “we’re not sure what took place in Lebanon”. That’s suggesting…well, my interpretation of that is that Lebanon had something to do with this. And I don’t think Lebanon had anything to do with it!

I don’t think this is about Lebanon, I don’t think this is about Islam; I think this is about Australia.

What’s Australian about it?

Look at Lebanese-Australian and Arab-Australian communities in Sydney, and look at the way they loved football. I mean, if they worshipped someone, I think those boys worshipped football players. I don’t think they worshipped God, in that time. I don’t think they were thinking about God or Islam. I think they were thinking about football. They were called Lebanese and Muslim in the media, but they didn’t live in a mosque, those boys. They’re Australian, those boys. They come home; they watch Australian television, when they go to a football game they go to a game where its Anglo-Australian players predominantly smashing into each other. And (these players) are their heroes.

Since 2000, there have been about a dozen allegations against these players who have been complicit in sexist, patriarchal and misogynistic behaviour and who have also been complicit in sexual assaults! So, why didn’t anyone say anything about that at that time the gang rapes took place? Why didn’t anyone say, “I wonder if there are links between the behaviour of NRL players and these young men?”

Or, you know, when Kyle Sandilands (more recently) asked a 13-year-old girl on the air if being raped was the only sexual experience she’d ever had. Why aren’t people asking about the impact that Kyle Sandilands has on Arab-Australian men? Or what about all the sexist things Tony Abbott says? Look at the way Julia Gillard was treated in the last three years.

Why aren’t people asking if our white male politicians aren’t having some kind of impact on the way Arab-Australian men are behaving? It’s not about taking away from the severity of their crimes – what they did was heinous and it was criminal and those men were brought to justice…it’s not about taking away from that – it’s about raising a more complex analysis of why those things take place and about asking all Australians of all races and all backgrounds to engage in this, and to work together to resolve the issue. Because I don’t think the issue is Muslims and Lebs.

Do you think we need to redefine what an Australian is? Is that part of the issue? That we have such a stereotypical view of ‘the Australian’ – White, ‘Aussie’ and so forth? And are we (non-White Australians) guilty of detaching ourselves from being ‘Australian’?

I don’t think we are detached. I don’t think we detach from our Australianness. I think we are rejected from our Australianness. Everything that is happening between us is Australian. My manner, my talking, my attitude, my opinions, my education – all of that is exclusively, and uniquely, Australian. You can’t find this anywhere in the world, this interaction. Everything that took place around us (just earlier) when that African-Australian kid just walked by, and that Vietnamese-Australian kid walked by, when all those things take place at the same time, and those cars go past with music pumping – one car’s pumping Arabic music, and one car’s pumping Tupac – all of that is uniquely Australian. There’s nothing that’s not Australian about that.

I don’t think we are detached. I don’t think we detach from our Australianness. I think we are rejected from our Australianness. Everything that is happening between us is Australian. My manner, my talking, my attitude, my opinions, my education – all of that is exclusively, and uniquely, Australian. You can’t find this anywhere in the world, this interaction. Everything that took place around us (just earlier) when that African-Australian kid just walked by, and that Vietnamese-Australian kid walked by, when all those things take place at the same time, and those cars go past with music pumping – one car’s pumping Arabic music, and one car’s pumping Tupac – all of that is uniquely Australian. There’s nothing that’s not Australian about that.

We have more than a stereotypical understanding of what it means to be Australian. We have a Eurocentric, a very Anglo-centric approach to understanding what Australian is. And not only does that exclude people of colour who have contributed to the building of this country, but, more importantly, it excludes the Aboriginal people who have been here for 60,000 years, who are the custodians of the country.

Ghassan Hage writes about how Muslims in Australia are ungovernable, and that’s the problem with us. We turn more to the orders of God than the laws of man, and so the fear of Muslims is that we might practice our Sharia. My question is what’s wrong with that? I had a Sharia wedding. And in a multicultural society, what is it to be multicultural? What White Australia says to us is: we like your food, we like your dancing, we don’t mind your clothes, when you’re not covering women in hijabs, but we like your belly dancing outfits, we like your music, we don’t mind if you guys want to speak Arabic at home, but that’s about as far as it goes.

Is it that they pick and choose what they want?

They take the things that are consumable. That’s the only thing they want, the things that enrich their lives. “We like falafel, and doumbek, but the things that actually push us to be a more equal society, those things we don’t want, those things we want to assert our dominance as the Anglo race”. And that’s what the flag says to me. The flag with the Union Jack in the corner, is asserting its dominance over us. The thing about Ghassan Hage’s point of us being ungovernable is that their behaviour was called un-Australian.

When there was a gang rape, when those Arab-Australians were jubilant and celebrating about the events of 9/11, when they were going to the beach and harassing those girls before the Cronulla riots took place, all of that was seen as un-Australian behaviour.

And that’s a way of distancing yourself from bad behaviour, but Hage says, with regards to those young men engaging with those women at the beach, that it wasn’t about being un-Australian, it was about being hyper-Australian…over-Australian!

Those young men, those Lebs we’re talking about, they go to the beach and go up to a girl and go, “Ay, come ‘ere, give us ya number, watta you talking ‘bout, come ‘ere,” – you know that guy? That guy is showing no shame. No shame at all, and the reaction from the Anglo-Australian community is, “Show some shame, have some dignity! What are you doing going down to the beach and harassing these women?”

What we’re talking about are young men who are so Australian that they’re not ashamed of it. They’re not ashamed to be what they are. They go around harassing people, asking some girl for her number and not being discreet about it. And that’s because they are very comfortable – I’m not defending their behaviour, don’t get me wrong – but what I’m saying is that is an exaggerated version of an Australian. That is not being non-Australian.

That is being Australian. You’re not going to find that behaviour in Lebanon. There’s a sense of dignity about that (over there), about what goes on in Lebanon. What we’re talking about here are young men who feel so comfortable in this country because they identify with this country.

Don’t you think it’s more of a universal issue? Misogyny and harassment isn’t just necessarily, or uniquely, Lebanese or Australian.

I think sexism, misogyny, patriarchy – there are layers. It’s a complex situation. In places where I’ve worked, you’ll see these middle class, heterosexual, White men who would never go up to a girl and say something like, “Ay, come ‘ere, give us ya number”, but what they would do, in a very subtle way, is objectify her. They would make passive aggressive remarks about how Arab-Australian women are exotic. They would actively reject women who don’t adhere to a certain appearance. They would be more inclined to hire a woman they find more attractive, but they would make it about her merits. That kind of sexism and patriarchy and misogyny is invisible. You get away with that, especially if you’re middle class and you’re educated enough to hide it behind some kind of educated approach.

I want to hear a bit about Sweatshop.

Sweatshop is fairly new. It was established in 2013. It is a movement that is devoted to bringing justice and equality to Western Sydney communities through literacy.

We produce publications, performances, we create videos documentaries, we run writing programs. We’re based at the University of Western Sydney. We have an office there, and we are funded by the Writing Society Research Centre. We primarily focus on marginalised communities in diverse ways and we are committed to the idea of self-determination.

For example, I think it’s important for Arab-Australians to be collaborating with other Arab-Australians. I think it’s important for women to be collaborating with women. I think it’s important for people from the LGBTQI community to be collaborating with the LGBTQI community.

I think that prevents processes of colonisation, where there are people in positions of privilege who are asserting some kind of dominance over minority groups. It’s about people from their own communities working with people from their own communities. And the other reason why we create that kind of culture is because we want believe that that’s the best kind of influence a mentor can have on a young person.

The best thing I can do for Arab-Australian men is being an Arab-Australian man. That’s something I don’t think any White male can do.

How do you, Luke and Peter know each other?

We’re writers who came together through our work as writers. I started up a writers’ group a decade ago – the early incarnation of Sweatshop. Peter and I were both working in community arts. Peter joined the writers’ group, but we had been friends before that. Luke and I met through our writing. He joined our writers’ group, and we’ve been collaborating, so we’re collaborators. Professional writers first and friends second.

The spoken word form – why that in particular?

Firstly, I want to distance myself from the performance poetry scene, like slam poetry, because I think that it is rubbish, with all due respect, because I think that (style) depends on being a good performer, and on being louder than the other person.

What we’re about is literature. Writing. Good writing. And what we’re about second is the performance. The reason why I became really interested in performance writing – writing that is supposed to be heard – is that for us, as Arab-Australians, we come from a very rich oral tradition. The best example being the Quran. The Quran is a written text now, but it was delivered to the Prophet Muhammad as the spoken word of Gabriel from Allah. And that is strongly connected in our tradition to literacy. When we talk about reading and writing, and literacy, we’re talking not only about physically writing on the page, but the oral ability to be literate too.

The Quran, the first verses that the Prophet Muhammad received in the Cave of Hira, Surat al ‘Alaq:

“Iqra bismi rabika alathi khalaq.”

“Read in the name of thy Lord, who created man from a congealed clot of blood. Read! And your Lord is Most Generous, who taught by the pen. He taught man that which he did not know.” (Quran, 96:1-5)

Teaching humankind with the pen, “read”; it’s a very poetic way of saying “speak” – speak this knowledge. In Islam and in Arab culture, there is a strong connection between the physical ability to write and the oral ability to speak. We don’t see those as separate.

So, the Prophet went to the people and said these words. And we believe that his miracle was that he was illiterate and then he became literate. That’s the miracle of the Prophet Mohammad, whereas with Jesus, it’s believed that he walked on water and raised the dead, with Moses, it’s believe he performed magic tricks. Our miracle is the miracle of literacy and education. But that miracle is not just about the written form, it’s about the spoken form – the Quran means ‘recite’.

It’s a very rich and very complex spoken tradition, which is about language, and writing and about education and knowledge. So I was really inclined to create and to fall into that tradition – to create words that are as valuable in the spoken form, as they are in the written form, which I think is a very European style of communicating.

So we make work that is to be heard. For people like me, it’s easy because it’s part of my history, for people like Luke, it’s a real struggle, but we’re getting there.

How long did it take to put together?

I started making it this time last year, so for 12 months. The first thing you do is have conversations, thinking of ideas, you have meetings, (attend) writers’ festivals, you write a few grant applications. You know, my rule is we never make a project unless it’s funded. And that’s the only way you avoid exploitation.

We’ve been working as writers for the last 11 months, but next week we become performers. We’re going to rehearse full-time until the show. There’s a lot of pressure because I think it’s a hard show to hear. It’s not a friendly show.

How do you think impacted communities have progressed over time? It’s been 14-15 years.

Why make it now? Well, because we’ve had 15 years as a country to really look into this and really open it up. We’ve had 15 years to start to understand why these things happen, and work to try preventing them, and I don’t think you can ever do that if you are going to vilify one racial group.

As a boy, I could only feel the pain. But now, as an educated young man, I can critique it and critique the issue of racial vilification in Australia. The very literal reason is because even though we’ve had a chance to investigate this as a country, as an intellectual country more broadly, instead, when Mohammed Sanoussi and “H” were released from prison earlier this year, the same language (was used)…”Lebanese”, “Muslim”…we haven’t come very far. Nothing’s changed. It’s been 15 years. And there’s nothing different about it. The media, the politicians, the police, they still have that same attitude – that the core issue is that these men are Lebanese and that they are from the religion of Islam, and so that’s why we’re doing this.

We’re here to say: yep, they did it, and yes, (some) young men of Arab-Australian backgrounds might be sexist and misogynistic and patriarchal, and we continue to see crime in those communities, but it’s not because of their religion and it’s not because of their cultural background. That’s what our work is about.

******

CATCH #THREE JERKS IN SYDNEY AND MELBOURNE. Watch the official trailer here.

SYDNEY

WHAT: Sydney Writers’ Festival

WHEN: Saturday, May 24, 2014

TIME: 3PM to 4PM

WHERE: Wharf Theatre 2, Pier 4/5, Hickson Road, Walsh Bay

COST: Book free tickets here.

MELBOURNE

WHAT: Emerging Writers’ Festival

WHEN: Friday, May 30, 2014

TIME: 7PM

WHERE: The Wheeler Centre, 176 Little Lonsdale Street, Melbourne

COST: $15 full/$12 concession. Book here.