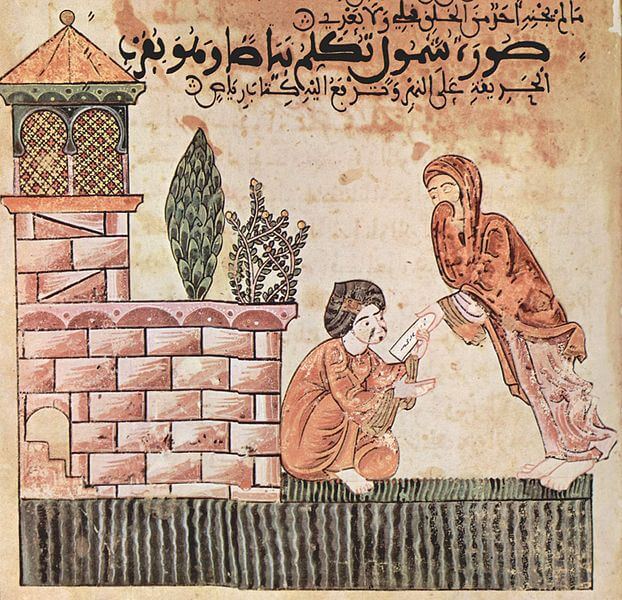

A page off a manuscript about the Story of Bayad and Riyad, which was approximately illustrated 8 centuries ago.

I wanted to be Britney Spears when I was thirteen years old. I couldn’t really dance or hold a tune to save my life but, really, neither could she, and her crop tops with cargo pants were just so on point.

I begged my parents to let me join dance classes and a singing group with my non-Arab friends. My mother said, “Ask your father”, after I annoyed her one too many times with my nagging.

I actually worked up the courage to ask my baba, and if you knew him at the time then you would know that asking permission for anything was a big deal. He would take a long pause, look at you sideways while rolling his cigarette, and make you wonder whether or not what you said was correct.

You see, he migrated from Lebanon to Australia in his late twenties and was determined to get us kids to speak Arabic even, much to our despair, in public. “Ask me in Arabic, and I’ll think about it,” he said.

“Forget it,” I replied, and sulked away muttering something under my breath about how they had ruined my chances of becoming a superstar. Growing up on Full House episodes, I had half-hoped he would come into my room later, tell me he was sorry and insist that I follow my dreams. But that doesn’t happen in real life.

Back to the hairbrush and bedroom mirror.

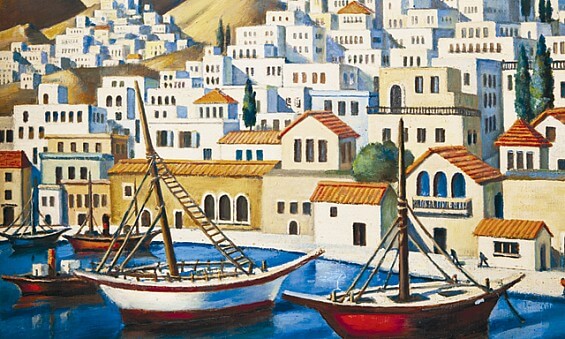

Mahmoud Said’s ‘View of Sirros’. Said, who is Egyptian, is considered the father of modern Arab art.

Looking back, I was obviously delusional, but Arabs have a rich history of celebrating the arts in all its forms: poetry penned by Khalil Gebran and Mahmoud Darwish, songs sung by Umm Kulthum and Fairouz, art created by Youssef Abdelki and Mahmoud Said, and films made by Zeina Daccache and Nadine Labaki. Or you could turn on LBC to look at all the wannabe Nawal Al Zogbe’s on Lebanon Idol.

Here in Australia, there are insanely talented Arab-Australian writers, musicians, and filmmakers. The question is, however, are they supported by the diasporic community in their lifelong aspirations? It was a question that I was determined to answer in my PhD thesis, which asked more broadly: what does it mean to be a creative person of Arab-Australian background?

I spoke with, and recorded the lives of, twenty-five young Arab-Australians working in the creative industry. We covered many topics, which ranged from schooling experiences to workplace discrimination. Overall, however, every young person I interviewed told me the same story: Arab parents, as Will Smith put it in his famous anthem , just didn’t seem to understand the desire to work in the creative arts industry.

“Shu hayda passion? Go be a dentist, make $80 dollars an hour and feed your family,” was a typical response when aspiring Arab-Australian artists expressed their interests to the family.

One young man who had gone on to complete a degree at COFA and now runs a small multimedia company told me of the devastating moment his mother put all of his artwork on the street for garbage collection. He got home from school and they were gone.

“She just didn’t understand that these came from a place of inspiration, in that moment, and they can’t be replicated,” he said.

For Arab parents, creativity is both useless and negative. Acting conjures up images of sex scenes, singing lead to drugs and partying, and painting – for young men – could mean you might not be heterosexual.

In order to understand the reasons for which Arab parents, and the broader ethnic public, perceive creative practices so negatively, it is imperative to highlight the visceral migrant experience. Most of the people in my study came from families where parents migrated to Australia from Lebanon as quasi-refugees due to the Lebanese civil war in the late eighties. They worked in low-paying, manual labour jobs in factories or on construction sites. Those who held qualifications in the Middle East were unable to have them recognised in Australia. They struggled to master the English language and experienced relentless racial vilification. It is these struggles that shape the way our parents engage in a discussion on careers for young people.

Arab-Australian actors (left to right): Rose Souaid, George El Hindi, Abbey Aziz, and Alissar Gazal on the set of webseries ‘I LUV U BUT’. Image by Fatima Mawas.

Many of these Arab parents worked long hours and seven days a week for as long as their children could remember – not for any intrinsic benefit or pleasure, but with the determination to provide stability and financial security for their children in the new country. As such, Arab migrants are determined to see their kids go to university, to have a better life, a different life from the ones they had.

Nonetheless, the young people in my study were immensely proud of their parents’ entrepreneurial spirit, as many of them now owned their own small businesses, such as takeaway shops, pizza bars, small goods delivery services, specialist leather repair stores, post offices, or were self-employed carpenters and tradesmen.

Thus, Arab parents have had to accept a career that isn’t ‘respectable’ – one with a professional title that is translatable in Arabic, like doctor, teacher or engineer to provide for their children. In fact, have you noticed, that everyone is an engineer according to your Arab parents? “Why can’t you study what Mohammed studied? Now he’s a mohandes,” they say.

Indeed, Arab-Australian youth who aim for social mobility tend to do so in fairly similar ways, usually via small business enterprises or completing degrees with ‘safe’ and financially secure career outcomes: see Mohammed the mohandes. That’s the case for a lot of migrant children. Research shows that the decision to choose such occupational positions is partly based on a desire to be seen as a ‘good’ migrant within the nation; that is, it is a way to overcome the stigma of the Other.

By contrast, creative careers are emergent and don’t follow a neat timeline, they feature bouts of unemployment and they don’t have just one title, which makes them difficult to explain to the community. Creativity, as a basis for a long-lasting career, is, therefore, foreign to parents and they are unsure about how to respond. Moreover, ethnic minority youth aiming to work in creative fields are vulnerable to racial prejudice and typecasting, meaning that their prospects for achieving commercial success is limited; parents have a sense of this limitation as they experienced discrimination themselves.

Ultimately, the young people in my study don’t celebrate their talents, but treat it as problematic – as something to work through. Creative identities are a site of struggle within the family because few others in the community are working in the arts, so one can’t just say, “But look at Salwa’s daughter – she studied at COFA and now she’s managing a gallery!”

When creative aspirants of migrant backgrounds do pursue their aspirations, they tend to produce works of art that redress the negative stereotypes of their communities, thus turning their lifelong, personal dreams as methods for redressing social inequalities.

In the era of the digital revolution, changes are happening. More youth from ethnic-minority backgrounds are finding spaces to be seen and heard, and to tell stories that are not only three-dimensional, but also move beyond creative expression in the ‘harmony day’ multicultural version prescribed by the state and sanctioned by traditional, religious Arab families.

It’s an exciting time, and I hope that we will see much more support for the arts in the next generation of Arab-Australians.

By Sherene Idriss

Sherene recently completed a PhD in cultural research at the Institute for Culture and Society and UWS. She writes about ethnicity, youth and identity and teaches Sociology and Anthropology.

Categories: Art, Culture, Religion and Culture