US President Barack Obama hosting the 2014 Ramadan iftar at the White House. By: Amanda Lucidon

During Ramadan, and in response to the bombing of Gaza, US President Barack Obama spoke at the annual White House Iftar. He called for both sides to come back to the negotiation table. Unsurprisingly, he went on to staunchly defend Israel’s right to defend its borders, claiming, ‘No country can accept rockets fired indiscriminately at citizens.’

Obama welcomed a crowd of important, invited and chosen dignitaries amongst American-Muslim leaders to an iftar had beneath a stunning golden chandelier. Reflective of the elitism and power of the occasion – miles away from the rubble of Gaza – he gave the typical, sentimental gesture of claiming commitment to peace, which was as similarly ornamental as the occasion of the iftar itself.

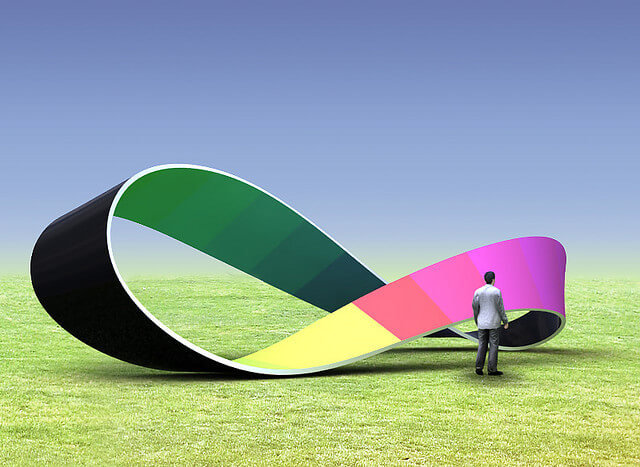

This enduring image of dialogue is like an elastic band that is stretched by two sides who are committed to debating without ever breaking the bonds that tie their communications. Such ornamental gestures of talking the-problem through, discovering friendships and exchanging respect through acknowledging differences ignore the reality that power, in fact, lays in the tensility of the language we use.

Analogously, it is the elasticity of the band that has the real power. For so long, it has only been stretched in one direction to speak about radicalisation, security and threat, and their antonyms of moderation, safety and togetherness.

Obama’s comments capture my point. His use of the word “defense” as belonging to Israel, an occupying force, might cause Palestinians – the occupied – to question whether more than just their land was taken. Their right to the word “defend” was taken away too. Palestinians are then, as a result, forced to explain themselves within a conversation about terrorism.

The mobius strip. By: Flavio Serafini

Understanding the conflict thus becomes as much about the Mobius strip as it is about the Gaza Strip. If we drew a line along the Mobius strip – a certain type of elastic band, a band of paper – without lifting our pen, we would return, uninterrupted, to where we began.

Despite the fact that the Mobius strip gives the illusion of having two sides or two surfaces, it only has one. So too does the violence of this conflict. There is no inside and outside; only a singular, outer surface that is the violence of illegally occupying Palestine. In this view, Hamas’ actions, logic and violence is as much an Israeli creation as it is Palestinian, and we ought to view it as analogous to a pen that has never been lifted. That is, there is no violence here that can assume an interruption as long as the occupation of Palestine persists.

The language we use today commonly denies this link.In Australia, the week before Ramadan ended with debates about disloyal youth flying off to illegally fight in Syria, and began with the horrible images of the bombings in Gaza. There was also little connection drawn between the two. When it comes to the history of the foreigner – in this case the Arab and or Muslim – they are always outside of sequences, systems, institutions and occupation, always outside the loop of history and context, and always the “other” side in a game of two.

Not surprisingly, Australia similarly holds what I term as “boutique” iftar events to promote dialogue between “two” sides. In the past two weeks, Melbourne and Sydney’s Muslim communities debated whether to attend the Australian Federal Police’s (AFP) invitation to an annual Eid dinner, considering the recently proposed changes to anti-terror legislation and the AFP’s appalling record in dealing with asylum seekers.

The debate is part of a larger discussion on whether Muslims should engage in the existing political system, as though, somehow, it is a choice. Those who call for a refrain from engagement also wrongly assume that there are “two” opposing sides when there is really only one form of power: the existing Islamophobic language through which Muslims find themselves negotiating their Islam.

The Australian National Imam Council’s (ANIC) announced boycott of the iftar is therefore to be understood as a long needed attempt – as far as I see it – to re-imagine rather than end the relationship with government. It is a way to introduce the less-than-boutique image of dissent to the dining table. (Editor’s note: Some members of ANIC were in attendance at the iftar despite the announcement.)

It is not, as some Muslims who attended the iftar might suggest in defence of their decision, a choice between “engaging” and “not engaging” with government organisations. The use of this simplistic binary only comes after the ideological pull of the word “engagement” has done its work and incepted their thinking.

Boycotting is a form of engagement. It stretches the co-ordinates of our debate by including our right to walk away when we feel the conditions of the debate are no longer suitable. Anyone who follows the tragedy of Palestine knows this intuitively.

Standing one’s ground during a dialogue with government is perfectly admirable so long as when a question of basic allegiance arises, one can also stay firmly on course by not negotiating the unthinkable, such as the further erosion of an already targeted minority’s rights.

Here, a pragmatist voice may return to ask whether the iftar is the best place to discuss politics. The excuses are typical – these events strengthen relationships, they celebrate similarities – and I confess they may well be that. But they are also more. They are a symbolic showpiece that is in itself a political act.

Walking away is also, in return, a symbolic gesture. It is a valuable bargaining chip that so many of our community organisations have, in my view, cheaply given away for a less valuable few million in grant money.

There needs to be a new conversation premised on new positions from where we converse.

Here, we can return to Obama’s flippant use of “both sides”. Framing it as a shared responsibility between two sides against a background of charred Palestinian bodies and buildings and an Israeli occupation sixty years long is a perfect way to obfuscate the reality that occupation is the founding violence that shapes all further violence.

Racism in Australia is our Mobius strip, then; it is the founding violence. It is an uninterrupted line of White anxiety that has continued this country’s commentary from the Indigenous Australian to the Muslim Other. The pen remains uninterrupted in the long history of ‘policing’ the Other, and we need to ask whether there is a suitable tensility in the current language of today’s “Good Muslim” dialogue surrounding the management of “Bad Muslim” radicalisation.

There may be no comparison between the suffering of Arabs in Palestine and the Muslims in Australia but there is a responsibility from Australian Muslims towards Palestinian Arabs, just as there are responsibilities to other minorities everywhere.

The mainstream acquiescence to Islamophobia helps us all turn a blind eye to problematic laws that will eventually strengthen the structures of exclusion for many others. Structures that are easily adapted for other ideologically “intolerable political subjects” like asylum seekers. Muslims need to adopt a language that separates the interests of the weakest from the anxieties of the majority.

I am left with this final thought of the Muslims on hunger strike in Australia’s detention centers, denied so many of their human rights. What would they think of their fellow Muslims’ halal dining?

Yassir is a post-doctoral researcher at the University of South Australia’s International Centre of Muslim and non-Muslim understanding.

2 replies»