Were the Mesopotamians a bunch of pessimists? Claudia Sirdah writes that Mesopotamian negativity is a product of their religiosity and their strong belief in fate – a mentality that can found in the literature they have left behind.

The Mesopotamians generally believed that the events of everyday life could not be explained on their own. Their philosophy was heavily shaped by their religious beliefs and promulgated a pessimistic worldview that revealed a struggle to understand the purpose and workings of life in the face of the gods.

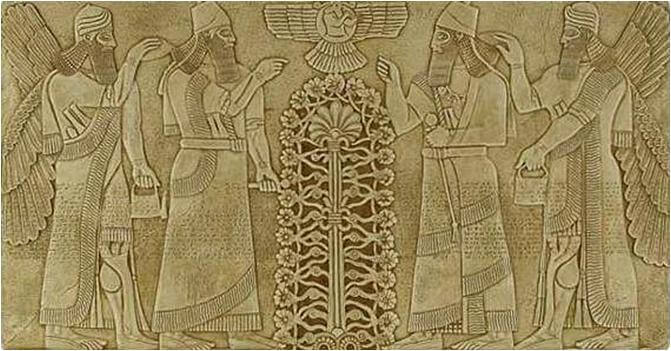

They believed that the gods – whose existence was beyond doubt – formed a supernatural society that both oversaw and were at the root of mankind’s affairs. So any fortunate or unfortunate event, be it political, material, social, or economic, was explained as having occurred by the will of the gods.

The Mesopotamians projected what they observed all around them onto a higher plane, and their literary and religious texts best capture their cynical cultural outlook. Literary sources such as laments, myths, and dialogues strongly emphasised man’s inevitable death. These also emphasise mankind’s powerlessness before the capricious gods and man’s inability to understand the human condition.

Man’s inevitable death

The famous Epic of Gilgamesh explores a myriad of themes, but, above all, is a didactic narrative of a great man’s failure to accept his fatal destiny. In it is a lesson to the audience: if this archetypal king – with his unparalleled strength, courage and superiority – could not escape death, then no one should imagine to do so. When Enkidu, Gilgamesh’s closest companion, dies, he receives a rude awakening – “Shall I die too, am I not like Enkidu?”

Gilgamesh is no longer blinded by a mirage of his permanence, which his power and luxury previously projected. Driven by a fear of death, he begins a quest for immortality. He travels to the ends of the earth to find a man, Utanapishti, whom he knows to have obtained it. After embarking on a perilous journey, he is approached the nymph Siduri, who says: “Gilgamesh, where do you roam? You will not find the eternal life you seek. When the gods created mankind, they appointed death for mankind and kept eternal life in their own hands”.

This is the most significant expression of the Epic’s main theme: the reminder of man’s impermanence. Siduri advises Gilgamesh to enjoy his life whilst he still can, because: “that is the only prospect for men”.

Nonetheless, Gilgamesh eventually reaches Utanapishti, who tells him that his own immortality was granted as a unique and exceptional situation. After observing Gilgamesh’s pain, Utanapishti informs him of a plant that would allow him to renew his youth and postpone his death. Gilgamesh finds the plant but a snake steals it, and so returns home having realised that all his efforts were futile. He then resolves to live life without giving the pursuit of immortality much thought.

Gilgamesh’s quest did not answer the wider ontological question of why humans are condemned to die, making his surrender quietly discomforting. The only answer, hinted by Siduri, is that it is because the gods kept immortality for themselves. But the message is clear, like Gilgamesh no individual will escape death.

The Mesopotamians’ fascination with death can also be found in Counsels of A Pessimist. This text is also didactic, and preaches the ephemeral nature of all human life and activity: “Whatever men do does not last forever, mankind and their achievements alike come to an end.”

The author explains that all efforts are pointless in the end and, in a fashion similar to Siduri, he gives the reader the advice to make the most of their time, but in worship, “As for you, offer prayers to your god, let your free-will offering be constantly before the god who created you.”

Another example of the emphasis of this theme lies in the lament The Death of Ur-Nammu: “I am one who has served the gods night and day, but what has been accepted of my efforts?” Here, even Ur-Nammu, who died prematurely, could not prevent his own death despite all his good works towards the gods. This renders the advice of the previous author even more disheartening, given that it is now suggested that it could make no difference – but such is the nature of Mesopotamian literature.

Powerlessness before the capricious gods

The divine sphere consisted of fickle gods. Overnight they could grant victory to the enemy or cause destruction without provocation. One example includes The Erra Epic, where the god of plagues becomes enraged because he felt ‘snubbed’ by the other gods, and destroys Babylonia as a result. The Lament for the Destruction of Sumer and Ur, however, is a text that best demonstrates how Mesopotamians understood the gods’ tempers. It opens with a description of how An and Enlil issued decrees that caused the Sumerian gods to abandon their cities, which were later destroyed.

The cities of Ur and Sumer were damaged so much it appeared as though they were “raked by a hoe”. The text then reads: “Its fate cannot be changed. Who can overturn it? It is the command of An and Enlil. Who can oppose it?”

This kind of helplessness is reiterated later: “The people sought counsel with each other, they searched for clarification: Alas, what can we say about it? What more can we add to it?’” The victims in this lament believed that they could do not mess with fate, and were confused as to the reasons behind the disasters.

During this time, their enemies, the Gutians and the Elamites, also attacked Sumer and Ur. Interestingly, however, the text says it is Enlil that sent them, and there are multiple references to these rivals being successful because they were ‘suddenly favoured’ by the gods. Nevertheless, when Suen, Enlil’s son, questions why Enlil has destroyed the city and whether he can restore it, Enlil replies:

“The word of An and Enlil knows no overturning. Urim was given kingship but it was not an eternal reign – who has ever seen a reign of kingship that would take precedence forever?”

Eventually, however, Suem intercedes once more for the city of Ur, and Enlil agrees to restore it. At no point in the lament is there a reason provided for the destruction of Sumer and Ur. Enlil gives no explanation other than the idea that no reign lasts forever, and it is only restored because of the intercession of his son. This lament reflects the resentful Mesopotamian mentality surrounding the nature of their gods; they believed them to be unkind, acting without reason, and cryptic in their motives.

There are also smaller incidents that express how people were afflicted in the face of divine abandonment and injustice. In the text Monologue of the Righteous Sufferer, the character is ill and finds none of his gods willing to help him despite the fact that he is pious:

“My ill luck was on the increase…I called to my god, but he did not show his face, I prayed to my goddess, but she did not raise her head.”

This divine abandonment perplexed the character since he felt he was being treated as though he had neglected the gods, which he hadn’t – “I, for my part, was mindful of supplication and prayer.” The sufferer then, similar to the inhabitants of Ur, cannot explain why this could be happening to him:

“Indeed I thought my piety to be pleasing to the gods! Who can learn their reasoning? Who understands the plans of the underworld gods? Where might humans have learned the way of a god?”

These rhetorical questions serve to illustrate that the Mesopotamians were unable to comprehend divine motivations and felt that they could not nothing but accept their predicaments. The suffering character knows that he will not understand why these unkind gods abandoned him.

He remains in an uncomfortable state: “My god has not come to rescue, nor taken me by the hand. My goddess has not shown me pity, nor gone at my side.”

The sufferer is not deserving of his pain, so these lines incite a feeling of divine injustice within the reader – something that may not come as a surprise to the everyday Mesopotamian.

Inability to know the meaning of life

This monologue, however, also hints at deeper issues of universal confusion amongst the Mesopotamians. “Who can learn the reasoning of the gods in heaven” has wide implications. The sufferer was devout yet still afflicted with calamity, which to the hero seems to be both an intellectual scandal and an incomprehensible enigma. What his narrative touches on is a theme addressing the inconstancy and perpetual contradiction that appears to rule all human activity. It raises questions such as “what is the meaning of life?”

The author of The Monologue does hint one thing: that none can know it because it is an understanding reserved for the gods.

Another work that addresses the metaphysical inquiry surrounding the understanding of the human condition is the text known as The Dialogue of Pessimism. The dialogue occurs between a master and his slave. Everything that the master proposes is met by encouragement and agreement by his slave, but when his master changes his mind the slave finds equally valid and strong reasons not to continue with the action. For example:

“Slave, listen to me! – Here I am, master, here I am!

– Quickly! Fetch me water for my hands: I want to dine!

– Dine, master, dine! A good meal relaxes the mind!

– [ ] the meal of his god. To wash one’s hands passes the time!

– O well, slave, I will not dine!

– Do not dine, master, do not dine! To eat only when one is hungry, to drink only when one is thirsty is the best for man!”

The rest of the dialogue includes similar conversation. The master desires to hunt, feast, marry, litigate and even revolt with the support of his slave, until he changes his mind and the exact opposite is justified. The dialogue triggers many metaphysical questions. Given that no one can be sure of their choices, because there will always be two opposing possibilities, a major problem is raised: what can we do in the end? Because what is good can also be bad, and what is useful can also be harmful, nothing is certain. The master, fed up with the contradiction, says:

— What then is good? To have my neck and yours broken,

or to be thrown into the river, is that good?

— Who is so tall as to ascend to heaven?

— Who is so broad as to encompass the entire world?

The philosophy here is pessimistic. When there are as many reasons to act as not to act everything becomes futile. The master questions: “what is the point of anything?” And so accepts philosophical suicide, because in the end there is nothing left but to renounce everything and “hit ones head against the wall”. But how does this relate? The answer lies in the lines: “Who is so tall as to ascend to heaven? Who is so broad as to encompass the world?”

These words capture more Mesopotamian cynicism, because what the master does by uttering these words is recognise that the universe is too large for him to understand and embrace, and indirectly poses that no one in this world can explain the meaning of human life.

Furthermore, the author returns to a Mesopotamian religious tradition: that only the gods, the masters of the universe, know and understand its progress; that only the gods can answer the innumerable and unsolvable questions we ask about the universe. This tradition is in no way restricted to The Dialogue only, as it was seen as an underlying theme in The Epic, The Monologue and The Lament. The Monologue and The Dialogue both come to the same metaphysical and philosophical conclusions. What they communicate is the idea that no can understand the meaning of life because it is part of the mystery of the universe. It is an understanding reserved for the gods, and like Gilgamesh’s pursuit of immortality, it is futile to attempt to gain it.

Overall, the texts discuss the inevitability of death, but they are not pessimistic for this reason. They are pessimistic because it is central to their texts.

It is another discussion entirely to examine to what extent these works reflect the beliefs of everyday Mesopotamians, but these common and reoccurring themes are not mere coincidences. The fact that the ages of the texts discussed range across the first to the third millennium, and come from different Mesopotamian cities, implies a strong continuity in their beliefs, as opposed to a short burst of negative philosophy that happened to be reflected in literature.

The attempt to unravel the mysteries of the universe and comprehend the will of the gods, inseparable from those mysteries, appeared to prove fruitless. However, the Mesopotamians, for the most part, accepted this. In summary, it appears that it is not too presumptuous to assume that the Mesopotamian cultural outlook was as follows: “We will die, experience hardship (possibly undeserved) and not know why, because the reason is not for us to know. Even after death the netherworld, the ‘land of no return’, was no cheery place to be: ‘the food there is bitter and the water brackish'” (Sandars).

They understood the netherworld as the ‘diametric antithesis of life’, and believed the netherworld had a complete absence of procreation and sexual intercourse and anything else enjoyable (Atac). Certainly, Mesopotamian literary sources depict Mesopotamian culture as being especially pessimistic.

By Claudia Sirdah

Claudia Sirdah is an aspiring historian and accidental earth scientist with an extremely unhealthy obsession with Tetris.

Categories: History, Religion and Culture

2 replies»