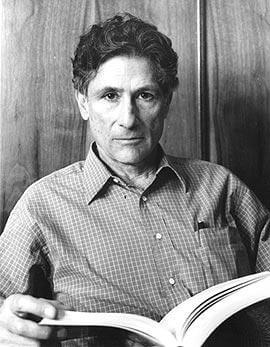

How does one begin to speak about the legacy of Edward Wadie Said? A teacher, professor of comparative literature, secular critic, literary essayist, voice of Palestine on my radio and in my newspaper during the 1990s, public intellectual who spoke truth to power, erudite writer and author with a boundless passion for knowledge who transgressed disciplinary politics and institutional etiquette. A scholar whose love and inquiry of literature, art and history gave us groundbreaking theoretical frameworks that have changed the course of curricula, culture and thinking, giving rise to new domains, disciplines, politics and movements.

Indeed, where to begin?

As a conscious ‘Saidian’, I begin naturally with questions from the man himself. Taken from one of the first of his published texts, Beginnings: Intention and Method, Said asks:

“What is a beginning? What must one do in order to begin? What is special about beginning as an activity or a moment or a place? Can one begin whenever one pleases? What kind of attitude, or frame of mind is necessary for beginning?”

What is special about beginning this activity, at this moment, in this place, is that we gather as a ‘community of the spirit’ – to borrow an inspired line from the poet Rumi – on the 10th anniversary of Edward Said’s passing to honour his existential presence; his being in this world.

The attitude or frame of mind I consciously bring to this task is one of love and a deep sense of feeling blessed that Edward Said lived his life in our time. A life of great importance, his intellectual eclecticism, his political activism and advocacy, his contribution to the world of ideas, his softly spoken words, the library of books he has.gif"text-align:justify;">Said’s thinking, essays, elaborations and commentaries, his public interventions and political engagement as an academic and intellectual who actually took a position, his dogged pursuit of justice in the name of Palestine threatened dominant paradigms. Taken together, Said’s corpus of work threatened the old guard as much as it continues to threaten the new guard. In effect, his textual presence threatened the hegemony of the master narrative and Anglo-Saxon canonical authority. In short, Said’s textual work eloquently undermines the very idea that there is one obvious truth. He, and many others who have been part of this embodied movement, which is referred to mostly as Postcolonial/Cultural Studies, has laid bare, in part, obscene power in all its manifestations of colonialism, imperialism, militarism, Zionism and racism.

For me, personally, Said’s legacy is embodied as lived practice in the realm of community cultural work. This space is important to so many of us; the emancipatory work that happens in the little spaces with community that aims for social change, political change, institutional change, cultural change.

Professor Said has especially made me mindful of the question of representation; self-representation and the persistent critique of representing others. As an engaged community cultural worker for the past two and a half decades, Said’s work on and off the page has influenced my own cultural and political engagement; his approach has informed how I work critically in a reception environment that is at once hostile to subjects who dare to speak for themselves in their own language and on their own terms; be they refugee, Palestinian, Indigenous, post-colonial or feminist narratives. In Said’s schema, an insistence on speaking for self and the responsibility to clear space ‘for those voices dominated, displaced or silenced by the textuality of texts… silenced by the systems of forces institutionalized by the reigning culture is of paramount concern.

Said’s masterwork, Orientalism: Western Conceptions of the Orient, published 35 years ago, inaugurated an exciting era of talking back to empire with self-affirming language, intellectual attitude, or in Said’s case – arabitude – and rigorous attention to a critical praxis that is conscious of power, agency and voice, tools fundamental to dismantling, disrupting, decentering systems, dogma and the hard rhetoric of the master narrative. The publication of ‘Orientalism’ and its journey across disciplines caused cultural and political ruptures, an unravelling of Western certainties about itself, its identity, and the so-called other. Indeed, as a mode of analysis and a methodology, the text continues to have sustained force and narrative amplitude across sectors, constituencies and disciplines despite the critiques, attacks and counter-narratives.

Whilst neo-conservative throwbacks insist on and revisit the primacy of white western foundational mythologies of terra nullius or the Israeli version of ‘a land without people for a people without land’ to authorise and legitimise dispossession via racist policies that exert economic political and linguistic power over the fate of the least powerful – and in the process affirming their own supremacy – Said’s critique of colonial will to power effectively unpacked how various modes of Orientalist knowledge have become productive sites of meaning, exposing the strategies, processes and devices that continue to have currency across cultural forms. His critical scrutiny of US foreign policy and the havoc it wreaks on the Arab world was most often the subject of his writings for The Nation, The Guardian, the London Review of Books, Le Monde Diplomatique, Counterpunch, Al Ahram, and al-Hayat.

Although the experiences of those whose dispossession continues into the present is painfully felt and fought in real terms and real time, our localised battles with the cultural gatekeepers whose colonial practices of totalising and essentialising the other in new Orientalist formations is at once a priority: be they powerhouse museums, screen culture or art galleries. Most recently, the City of Sydney’s Art + About program monologically reduced an entire history of colonial dispossession by hosting an Israeli military photographer as visiting artist. Hoisted on the poles of downtown Sydney, banal banners with text denote the cities of the world. All very well until you hit the pole that states in bold font, ‘Jerusalem Israel’. And so, as the silky banner wafts in the idle wind, the erasure of Palestinian dispossession – the material theft of land and property, gardens, graves, chairs, tables and household goods – is made invisible. As is the expropriation of East Jerusalem homes and properties owned by Palestinians in the here and now, with scenes of violent evictions of Palestinian residents and the enacting of racist policies by the Israeli state not to be discussed in the polite environs of the Artist Talk.

Some still wonder in their somewhat disembodied little world if art is separate from politics. Can you imagine a Palestinian artist hoisting her banner, ‘Jerusalem/al-Quds, Palestine’ up a Sydney pole so effortlessly?

In reflecting on Said’s legacy as an embodied practice, the persistence of Orientalist ideology and hyper-activity has thus produced a particular type of critical subjectivity in diasporic communities. As a cultural producer in community-based settings, I am especially conscious of an ethics of representation even while self-othering and self-orientalising constitutes a ‘normalised’ practice in everyday multicultural contexts; nothing if not complicit in and with colonial representational demands that maintain the asymmetries of power.

In revisiting the terrain of representation in Culture and Imperialism in 1993, Said’s words are glumly indicative of the endurance of Orientalist logic today:

“All roads lead to the bazaar; Arabs only understand force; brutality and violence are part of Arab civilisation; Islam is an intolerant, segregationist, ‘medieval, fanatic, cruel, anti-woman religion. The context, framework, setting of any discussion [is] limited, indeed frozen, by these ideas”

Finally, a word on Palestine from one of Said’s many inquiries and meditations on Palestine and Palestinian identity. From The Last Sky: Palestinian Lives, Said writes:

“We are a people of messages and signals, of allusions and indirect expression. We seek each other out, but because our interior is always to some extent occupied and interrupted by others – Israelis and Arabs – we have developed a technique of speaking through the given, expressing things obliquely and, to my mind, so mysteriously as to puzzle even ourselves.”

And in Reflections on Exile, Said writes:

“The exiled knows that in a secular and contingent world, homes are always provisional. Borders and barriers which enclose us within the safety of familiar territory can also become prisons and are often defended beyond reason or necessity. Exiles cross borders, break barriers of thought and experience.”

I often wonder what Professor Said would make of events of the recent past – of Tunisia, Egypt, Libya and Syria. Perhaps, a clue can be found in his 1993 Reith Lectures, Representations of the Intellectual, where he describes how “the intellectual must remain a dissenter, never putting solidarity before criticism, and must speak from the margins for both the people and the issues which are routinely forgotten or ignored”.

So many volumes of words devoted and dedicated to the life, writings and activisms of Edward W. Said have been published since his death. As Jean-Luc Nancy affirms, “Community is revealed in the death of others; hence it is always revealed to others”. Whether they are the words of thinkers and writers like Joseph Massad, Jacqueline Rose, Ilan Pappe, Ella Shohat, Adel Iskandar, Judith Butler, Ahdaf Soueif, Hamid Dabashi, Cornel West or people like us, what we share is love and respect for an individual whose life work has irrevocably changed the way we think, see and speak; how we are in the world.

Said’s legacy binds us as a ‘community of the spirit’; a community of dissenters, a community insisting on the universality and indivisibility of human rights, a community committed to speaking truth to power, to challenging and disrupting symbolic and real systems of oppression in creative, radical ways.

We walk the Saidian path towards change with a footnote from us all:

Thank you, dear Edward Wadie Said.

Shukran, for your presence in this world; for your love of knowledge, for your generosity in sharing that knowledge, for your elegant writing, for all the books under my bed, for your relentless pursuit of justice for Palestine and Palestinian rights, and for giving us the intellectual hardware and clarity of purpose to begin.

Allah yerhamo.

References: Nancy, JL., ‘The Inoperative Community’, University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis (1991); 15.Said, E.W., ‘Beginnings: Intention and Method’, John Hopkins University Press: Baltimore 1975).Said, E.W., ‘Culture and Imperialism’, Vintage: New York (1993).Said, E.W., ‘Orientalism’, Routledge & Kegan Paul: London (1978).Said, E.W., ‘Reflections on Exile and other Essays’, Between Worlds, Harvard University Press: Cambridge (2002).Said, E.W., ‘Representations of the intellectual: The 1993 Reith Lectures’, Pantheon: New York (1994). Said, E.W., ‘The Last Sky: Palestinian Lives’, Colombia University Press (1999).

By Dr Paula Abood

Categories: Politics