As it has been 10 years since the passing of Edward Said, one of our best modern thinkers and public intellectuals, it is imperative to examine how his work has influenced both his and my generation – specifically in our understanding of the relationship between Orientalism and the colonisation of Africa.

Said’s epistemological and ontological mind has, and continues to, fascinate other public intellectuals, students, politicians and spiritual leaders in our society. His in-depth understanding of the international system, through his studies of history, art, culture, music and political science has helped people map their theories and further their understanding, of international relations and justice. In particular, Said enabled people to understand the reason/s state and non-state actors behave in certain ways and, perhaps most importantly, the forces that major powers keep in place to maintain the status quo; that is, the manner in which major powers create an image of the world that best serves their agenda.

Said’s academic contributihas played a huge role in critical theory and power discourse, as well as provided an understanding of the world during, and after, colonialism. He has, of course, written many books, articles, seminar papers and given hundreds of lectures about various international issues, particularly his lifelong desire to see the Palestinians gain their right to self-determination. But Said’s most controversial yet powerful book, Orientalism, is explained through the narrative of Black Africa.

Orientalism, which was coined in 1978, means the study of the Orient – in this case East Asia and North Africa, by the Occident (the West). The book discusses the manner in which historians, writers, artisans and political scientists from the West have, in various forms, depicted the Orient in a rather patronising and self-serving fashion. Specifically, the Orient has been portrayed as a society that is backward, brutish, underdeveloped and in need of modern or Western enlightenment.

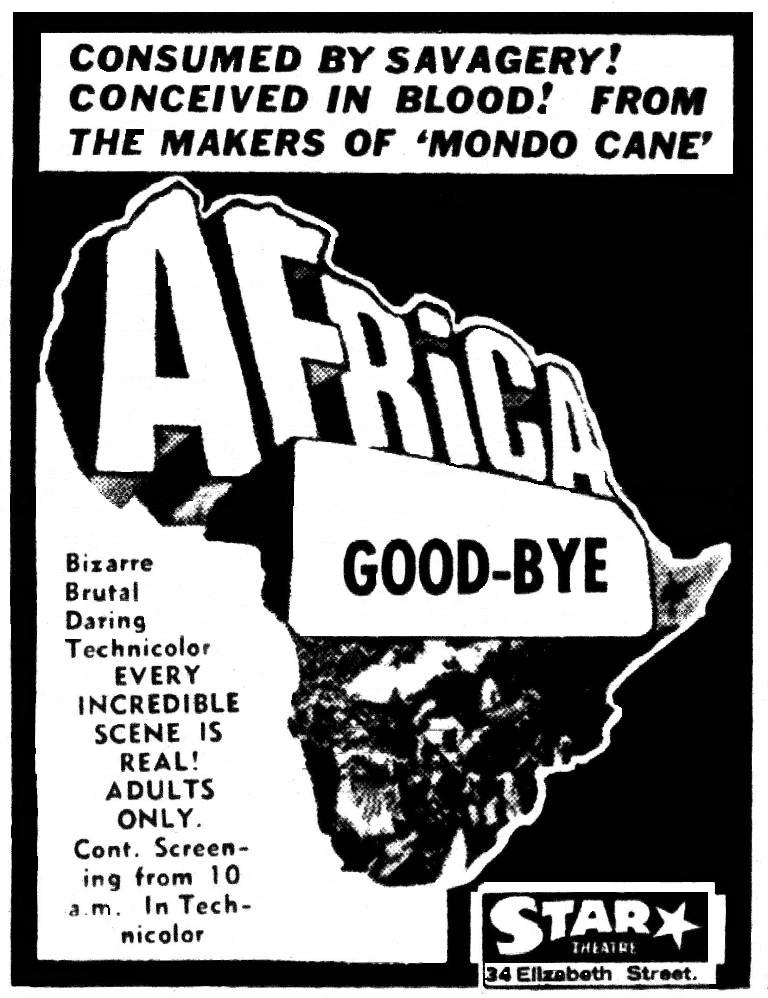

The Occident, however, is seen as culturally advanced, greater, sensible, rational, and exceptional! These false fabrications of the Orient are then continuously reinforced through various forms of artistic works by the Orientalist: textbooks, such as Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, which dehumanises Black Africa; Victor Hugo’s Les Orientalis, which explained that the aim of Europe in the 19th century was to ‘make a man of the blacks’ and civilise old Africa; scholarly articles, such as the publication of an article titled Africa the Hopeless Continent by The Economist, and also films like Tarzan depicting Africans as savages who know nothing about civilisation.

Once these powerful myths are inserted into Occident culture and infiltrate the minds of the Orientalist, it is not surprising that Black Africans are then stereotypically perceived by the general public as being backward, savage and other descriptions in the same vain. These false depictions of Eastern and African culture led Said to assert:

“Orientalism, therefore, is not an airy European fantasy about the Orient but a created body of theory and practice in which, for many rations, there has been a considerable material investment. Continued investment made Orientalism, as a system of knowledge about the Orient, an accepted grid for filtering through the Orient into Western consciousness, just as that same investment multiplied-indeed, made truly productive-the statements proliferating out from Orientalism into the general culture.”

Colonialism and imperialism would, therefore, not have been made possible without the reductive statements, and false fabrication of knowledge, about Black Africans; that is, to list a few, Black Africans are a people who are not as capable of governing themselves as the Occident, a people who belong to a primitive culture as compared to the Occident, and a people that have formed a type of civilisation that by no means provides them with a good system of government relative to the Occident.

To get an understanding of the origin of Africa’s political instability, it is imperative to examine the historical developments and changes that took place before and after colonisation as a result of Orientalism. It is only through these phenomena that one is able to encapsulate the economic and political crisis that ravaged the continent since the implementation of the concept of nation state.

Before the 19th century, the African interior was of little or no interest to the European – so long as they were able to pursue their interest through the African middlemen (to obtain slaves). During the petition of Africa at the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885, which saw the division of the whole continent by the European powers into separate colonies, there was a clear consensus amongst the European powers that African people are culturally and biologically inferior and in need of European enlightenment to remove the continent and its people from ‘darkness’. These racial prejudices by the European leaders, and powerfully condescending views of Africans at the onset of colonialism, were, to a large extent, imported from European writers and scientists.

As a result, Charles Darwin and many other intellectuals of the time believed that Western cultural superiority was at the zenith of African culture and that, therefore, Africans by nature should be dominated and controlled. These persuasive yet false intellectual descriptions of the Africans remind me of another passage in Said’s Orientalism:

“Once again, knowledge of subject races or Orientals is what makes their management easy and profitable; knowledge gives power, more power requires more knowledge, and so on in an increasingly profitable dialectic of information and control.”

Knowledge does not need to hold an absolute truth in order for it to be powerful, its persuasive element is what enables it to be powerful. And power, to quote Walter Rodney, is:

“…the ultimate determinant in human society…..it implies the ability to defend one’s interests and if necessary to impose one’s will by any means available. [Thus] when one society finds itself forced to relinquish power entirely to another society that in itself is a form of underdevelopment.”

To support Rodney’s definition, Said wrote:

“The relationship between Occident and Orient is a relationship of power, of domination, of varying degrees of a complex hegemony.”

The colonial, economic, and political structures were the engine that kept the dominant power relations running. On the economic front, through Structural Adjustment Programs (SAP), policies implemented by Occidental institutions proved disastrous for the African continent. The condition of such policies required the African economies to remove all barriers to trade, devalued their currencies, relaxed employment in the public sector, increased interest rates and curtailed government spending on policies that are garnered on social welfare.

Despite the fact that the Western pioneers of such policies were calling on the African continent to liberalise African economy, they maintained their protectionist policies that contributed to derailing the African export market. And, on the political front, with all the claims of seeking to promote democracy and transparency in Black Africa, the Occident installed puppet regimes that served their interests.

Hence, Said’s major influence on me personally has been on the way I look at reality. Said has enabled me to rethink the legacy of colonialism and how its significant repercussions on Africa are still present today in varying forms and structures.

References

Rodney, W., ‘How Europe Underdeveloped Africa’, Bogle-L’Overture Publication: London (1981), 224.

Said, E. W., ‘Orientalism’, Routledge & Kegan Paul: London (1978).

Karamzo Saccoh

Karamzo is the founder and director of the Australian Council on African Affairs.

Categories: Politics

Reblogged this on sfalmohammadi.

Like Like