In the wake of the recent terrorist attacks, and the premiere of The Hunger Games: Mockingjay Part II, Batool Al Sallakh writes about using the dystopian genre as a means of influencing activism…

The world is changing.

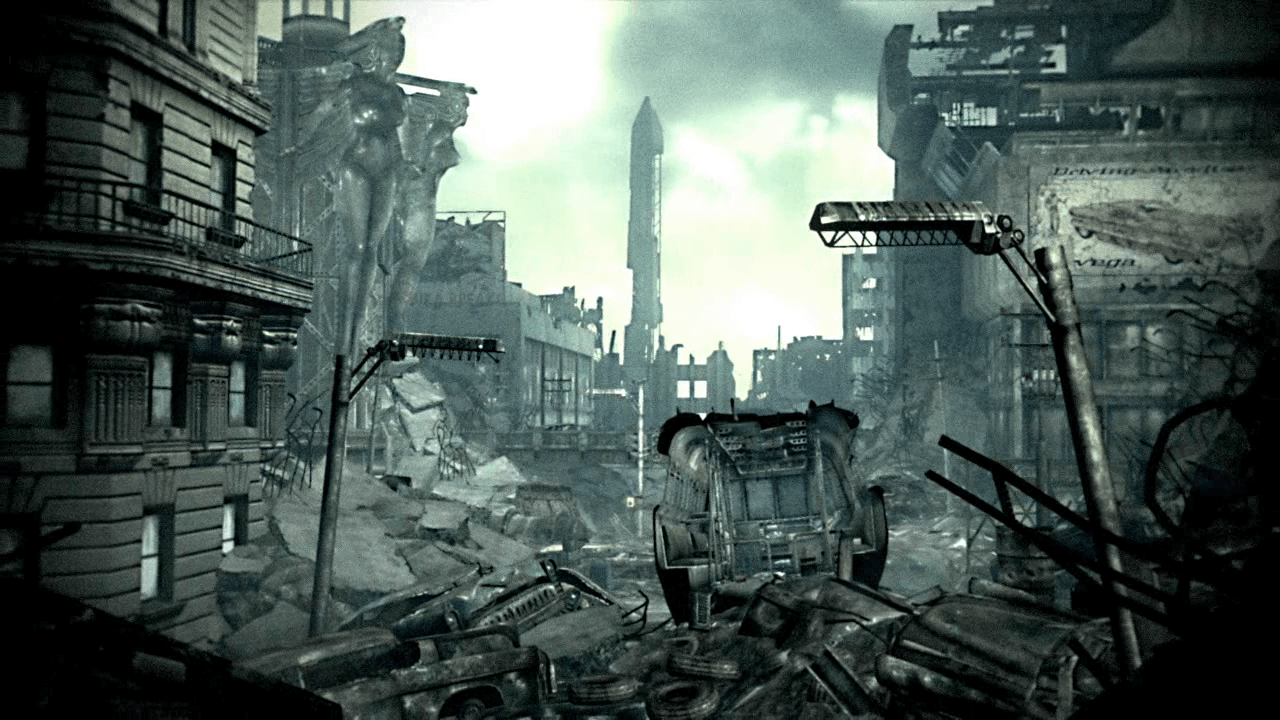

Events currently occurring around the world will be studied for generations to come. Our reality is now akin to a dystopia. And, although dystopian novels bring to the fore extremely important socio-politico issues, which should encourage introspection in readers, we have not heeded the advice presented in those stories.

Events currently occurring around the world will be studied for generations to come. Our reality is now akin to a dystopia. And, although dystopian novels bring to the fore extremely important socio-politico issues, which should encourage introspection in readers, we have not heeded the advice presented in those stories.

A ‘dystopia’ is an unpleasant fictional society, often associated with the future. The genre seeks to discuss the effect of totalitarianism, materialism, environmental disasters and man-made catastrophes, on society. Famous examples of these novels include The Hunger Games trilogy by Suzanne Collins, the Divergent series by Veronica Roth, and The Maze Runner trilogy by James Dashner. The theme of each series centres around a protagonist who lives in a dictatorial regime, whereby fear and manipulation are the norm. Eventually, a disastrous event occurs, thus forcing the protagonist, and the society in which they live, into a revolution to restore peace and order.

Indeed the dystopian genre carries with it a key message: this ‘fantasy’ world is in actual fact a reality.

The ominous theme of these novels should, therefore, serve as a catalyst for conversations about world events, such as the recent violence in Paris, Iraq, Beirut, and, perhaps more importantly, facilitate an understanding of the causes underlying such situations vis a vis a fantastical world.

However, readers don’t seem to make use of the message or draw those connections.

The Hunger Games could be presented as a representation of Syria. The story includes characters who identify as ‘The Capitol’: they are a populous who live in luxury, obsess over the latest trends and watch the Hunger Games; where children from all twelve ‘Districts’ (cities) fight each other to the death, until there is one child left standing. In contrast, there are characters who identify as being from the Districts: they are a populous who live in poverty, and have little control over the manner in which their lives pan out; they work to provide for the Capitol.

The Hunger Games could be presented as a representation of Syria. The story includes characters who identify as ‘The Capitol’: they are a populous who live in luxury, obsess over the latest trends and watch the Hunger Games; where children from all twelve ‘Districts’ (cities) fight each other to the death, until there is one child left standing. In contrast, there are characters who identify as being from the Districts: they are a populous who live in poverty, and have little control over the manner in which their lives pan out; they work to provide for the Capitol.

Whilst watching The Hunger Games: Mockingjay Part 1, I thought of the Syrians. Disturbed, I watched on as the movie depicted a dictator bombing, killing and destroying his own people.

One scene in particular struck a nerve. It was when Katniss Everdeen (the protagonist) visited a field hospital in a city that President Snow (the antagonist) had attacked. Shortly after she leaves, the field hospital is bombed. Hundreds of innocent people died fighting for their basic human rights.

I felt sick. Here I was watching this film for enjoyment while my own people were living this hell.

We should be putting these novelisations into perspective.

Imagine Syria as a District; the people are living under a dictatorship with President Bashar Al Assad, and imagine us, who are on the outside, as the Capitol. While we don’t watch children being killed for entertainment, we do stand by as silent witnesses to the atrocities occurring on a daily basis.

But, we do not only stand by idly as over 200, 000 Syrians are slaughtered, but we also forget about the 5 million Palestinians in need of aid since the 1948 occupation, and ignore the mistreatment and murder of unarmed black people by police in the United States and Aboriginal people at home.

The issue lies in our reaction; how is it we can finish a book or movie like The Hunger Games, shudder, then shrug it off and commence to discuss the extent to which the main character is attractive? Why is it “just a story” for us? We sit comfortably in an air conditioned cinema with popcorn and watch this ‘fantasy’. We forget that, for many in the world, this fantasy is a reality.

The issue lies in our reaction; how is it we can finish a book or movie like The Hunger Games, shudder, then shrug it off and commence to discuss the extent to which the main character is attractive? Why is it “just a story” for us? We sit comfortably in an air conditioned cinema with popcorn and watch this ‘fantasy’. We forget that, for many in the world, this fantasy is a reality.

Is our reaction driven by our desensitisation to violence and injustice? When reading about characters from the Capitol in the Hunger Games, we pity their naivety and find their ignorance frustrating, but instead of simply hating these characters, we should be engaging in a process of self-reflection.

How has our society not taken the true message of the dystopian novel? We seem to blur the lines between what is real and what isn’t. While obviously there are differences, the core themes are the same; and authors of the dystopian genre address issues that are happening to us as a collective community.

With the dystopian genre holding such a powerful stance, it should be used as a tool of empowerment to influence political action. It should inspire people to at least think about their position and role in society, instead of simply ‘enjoying’ the film.

The next time you watch or read a story from the dystopian genre, you should turn your thoughts to the more important issues in our world, and think about whether or not you are merely a passive viewer or taking an active role in changing our collective present.

By Batool Al Sallakh

Batool is a Syrian-Australian student at the Queensland University of Technology. Studying law and journalism, she is a brilliant combination of laziness and determination. Most of her time is spent on ASOS, YouTube and Twitter. Conversing about Middle Eastern politics with Batool is ill-advised, although she has learned to tone it down over the years. She has issues with table manners and will not respond if you start a conversation with her in a cinema.

Categories: Art, Literature, Politics