As Refugee Week draws to a close, Amina Youssef writes about the need to remove asylum seeker children from immigration detention …

War and conflict are always sad. They result in the destruction of homes and livelihoods, the fractioning of communities, and the end of peace and stability. In the midst of all fighting and turmoil are children, who are not only vulnerable, but are likely to find themselves living in refugee camps, thrown on boats or, even worse, in detention when their family begins to search for security elsewhere. These children do not belong in refugee camps, let alone in immigration detention.

The report from the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention, which was released in 2014, revealed nothing to us that we didn’t already know. Children are suffering both physically and psychologically in immigration detention – to an extent that it can only be described as government sanctioned child abuse. According to statistics from March 2014, a child spent on average 231 days in an Australian immigration detention facility. These facilities were not safe nor appropriate. In fact, the inquiry found that children in detention are susceptible to sexual abuse and harassment, and the closed detention environment had led to 128 incidents of self-harm.

It’s hard to believe that these distressing events are occurring with the knowledge of the Minister for Immigration, who is the Legal Guardian for unaccompanied minor Asylum Seekers. It’s ironic and sad, since he is also the head of a government policy that permits their oppression. The UN Human Rights Chief slammed this policy last year in his opening speech to the UN Human Rights Council, where he accused the Australian government of committing a “chain of human rights violations”.

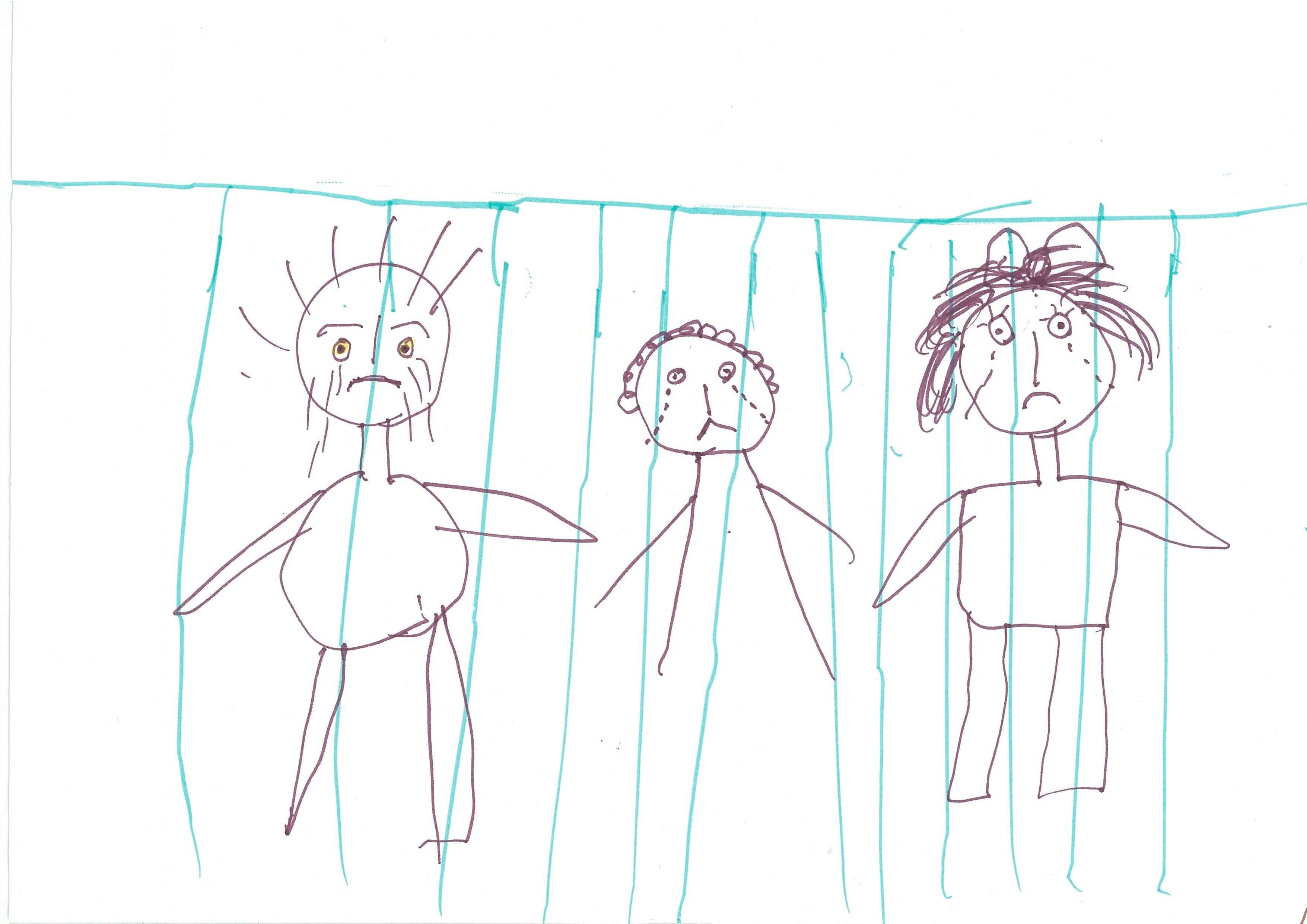

Many of the drawings submitted to the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014 depicted children in jail. Image: Australian Human Rights Commission.

It must be immediately recognised and accepted that children do not make the decision to travel on boats, and, therefore, should not be punished for a decision that was not made by them. According to ChilOut, there are still children being held in detention on Nauru, Christmas Island and in other facilities within Australia. As a party to the Convention on the Rights of the Child, Australia has a duty to act in the best interests of the child and to ensure their needs are met. As a result, Australia should immediately remove all children from detention and discontinue its shameful policy on asylum seekers.

But, it is also important to recognise that Australia is not the only place where children seeking asylum are suffering. In other parts of the world, children are regularly and heavily affected by conflicts around them.

According to UNICEF, Syrian refugee children as young as seven years of age have entered the work force in Lebanon, while in Jordan they are breadwinners for almost half of all families surveyed. In Myanmar, unaccompanied Rohingya children are forced to flee on boats in dangerous situations; they spend days without food and eventually end up in foreign camps without their legal guardians. Reports of the children remaining in Myanmar refugee camps have included unprecedented levels of children experiencing severe malnourishment .

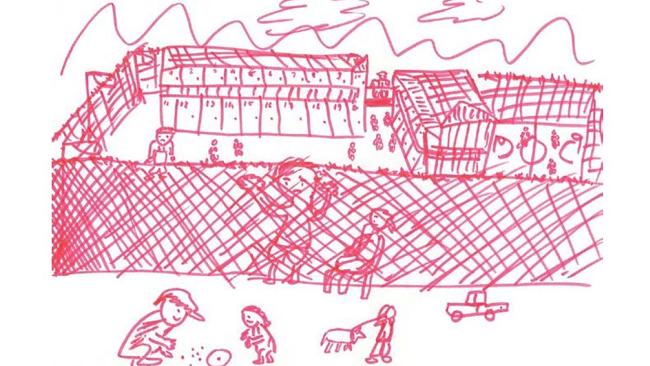

A child draws themselves watching other children play from behind a detention centre fence. Image: Australian Human Rights Commission.

No situation is more bleak, however, than that of the forgotten conflict of the Central African Republic (CAR). Despite the barbarity of crimes involved in the conflict, including reports of cannibalism and massacres, the war never really captured the attention of people around the world. Children were recruited as child soldiers while others were sexually abused by peacekeepers. In further demonstration of the brutality that the conflict caused, six out of 10 children in the CAR are now suffering from PTSD – a n entire generation of children ‘traumatised’.

I could go on and on about the pain and distress caused to children by the war and conflicts around them before they even become refugees or asylum seekers. But all of these stories and experiences lead to the same conclusion: we – people living in secure foreign nations – need to do more to recognise and protect children who have become refugees and asylum seekers as a result of problems over which they have no control. Indeed the root of the problem could be fixed by ensuring their homes are safe and secure, but that is not a solution in which the foreign nations can always partake.

Ultimately, all we can do is be willing to provide protection when they decide to flee.

By Amina Youssef

Amina is a Sydney-based lawyer and human rights activist. She tweets from @mina_ysf.

Categories: Politics