Everyone has at least one crazy uncle. I have about six. Without airing my family laundry, it would be fair to say that I grew up in a pretty strange household, where I witnessed all sorts of weird behaviours and occurrences. Now, this isn’t to say that the following list of family-related idiosyncrasies are exclusive to Arab families, but there is an Arab touch – whether cultural or linguistic – nevertheless.

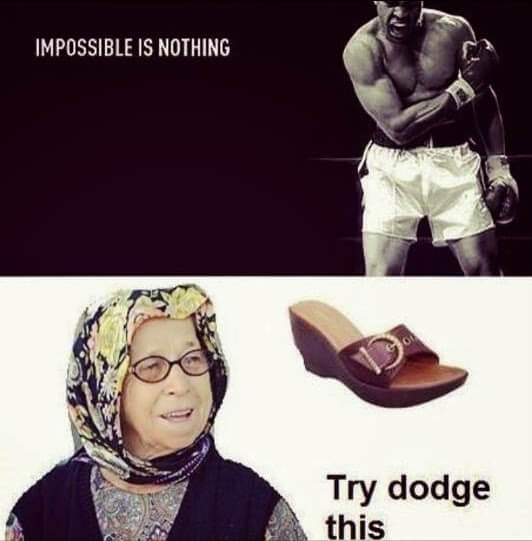

The maternal shoe launch

If you were born into an Arab family, or have ever witnessed an Arab family in the throes of one of their melodramatic, chaotic arguments, you should know exactly what I’m talking about. That instant in which your mother decides that patience and reasoning simply will not do anymore, then proceeds to take off her shoe and launch it at you, her selected target.

What astonished me most about my late mother’s habit of shoe-launching is the detached and deadly precision of her aim, despite the irate frenzy she appeared to be in. One time during an argument that couldn’t be resolved, I saw my mother reach for her shahayta (the Arabic colloquial term for sandals). My self-preservation instinct propelled me up the stairs in huge three-step strides. As I was about to land on the second floor and proclaim my narrow escape, I felt the dull but weighty impact of my mother’s shahayta on my backside.

Arab parents’ colourful and sometimes downright morbid ways of scolding their kids

I’m not so sure I should be writing about this as it divulges perhaps a little too much Arab domestic dysfunction than might be considered polite. But, anyway, here it goes: Growing up I never thought twice about it, but age and hindsight has endowed me with the ability to look back and critique my family’s style of communicating. There were plenty of virtues, but one thing staring me in the face was the bizarre collection of insults and reprimands that I had stored in my memory, which had been directed both towards me, my siblings as well as other relatives and friends. To clarify, my parents did in no way act upon these theatrical threats/insults- it is simply a part of their vernacular.

So, for instance, in the many occasions when my dad was really irritated with someone, he would say in Arabic: “Be quiet, or I’ll step on your stomach”. Another common insult used was “lick my foot” and “lick my ass”. The very popular Arabic insult kess imak – which translates in English to “vagina of your mother” – was also a favourite.

There was also a more elaborate version: kess imak bi ejri, ‘ars, which literally translates to “vagina of your mother in my foot, pimp.”

More innocuous ones I heard were Ya hakir (“You low-life”), Baghal (“mule”), and debeh (“sow”).

There was also no shortage of excessive, but empty, threats: once during a very heated argument with my mother, she turned to my brother and said “Go fetch me the axe!” – with which she was going to presumably murder me. My brother and I looked at each other for a moment then started cackling like hyenas.

Reflexive address

One day when an Anglo-Australian friend was over, she listened as my dad asked me to fetch him a glass of water. She noted that he addressed me as Baba, which is the Arabic equivalent to daddy.

Turning to me with a quizzical expression, she asked: “Zena, why is your dad calling you daddy?” Explaining this feature of the Arabic vernacular was especially difficult for me at the time because I hadn’t ever thought about it consciously.

“Er…” I fumbled, “It’s…if someone is your dad, they can call you ‘dad’ in Arabic, because they’re…your dad.”

“Oh. So your mum can call you mummy, too?” She asked, trying to process my inarticulate explanation.

“Yep!”

“And your uncle can call you ‘uncle’?”

“You got it!” I said happily.

“So can you use the reflexive address as well, like can you call your dad ‘daughter’?”

“Ah…no.”

Irrational rationalisms

Perhaps your parents have subjected you to their irrational sense of logic too. I grew up in the 90s, so there were a lot of trends and norms at the time of which my mother didn’t approve of.

The internet was perceived as a diabolical force of degeneration that should mostly be strictly avoided, much like television was in its initial heyday.

“IT WILL MAKE YOU ANTI-SOCIAL AND PREY TO DISGUSTING OLD PSYCHOPATHIC PERVERTS. Haven’t you read the story about the man who was chatting to a teenage girl on ICQ and when they met he raped and killed her?” my mother would rage hysterically.

My dad would wax lyrical about the existential dilemma posed by the rise of the internet as a means of communication. “People will simply stop communicating in person. We will all isolate ourselves in our cells and communicate online. It will be a dystopia of the highest order.” So fearful were my parents of the internet’s destructive influence, they took to hiding my modem (this was in the good ol’ days of dial-up).

I was allowed to use if for one hour a day on weekdays, which of course only made it all the more alluring. Once I’d found my mother’s hiding spot (usually she’d stuff it in one of her satin evening purses), I’d reconnect to my beloved internet, piling pillows, blankets and doonas on top of the modem to drown out the ringing, swoosh-bleep-bling-swoosh sound.

Irrational rationalisms could also be found in my parents’ attitude toward my newly pierced upper ear when I was 14, from which a large black sleeper earring hung. “This is not nice. I do not like it”, Mum declared with disgust.

“But why? It’s just fashion,” I’d say.

According to mum, earrings that dangle conventionally from the lobes were far more palatable and bespoke of moral uprightness and exemplary behaviour. Earrings anywhere else? Indecent, weird, ugly, unconventional and what will people think? She was so certain of the earring’s indication of debasement that I eventually took it out because every time I looked in the mirror, her voice would echo in my head: “Oh god…please, Zena, I can’t. I just can’t look at it.”

It’s true. I grew up in a highly dysfunctional Arab family. But it’s not without its perks. I’ve got hilarious anecdotes for days that when recounted have left my friends and I with tears streaming down our cheeks, bellies aching with laughter. My Arab family was noisy, dysfunctional, sometimes highly embarrassing, but now, older and living independently, it exists in my mind as a haphazardly created collage of colourful memories, like the smell and wonderful sight of my mum’s cooking, my dad’s roar of triumph while playing tawlit el zahir (Backgammon) with his friends, uproarious political discussions over the perpetual backdrop of Arabic news, my brothers’ tricks and pranks during our pumpkin-seed filled barbeques, doing (or pretending to do) the dabke at Lebanese weddings, and the music of Fairouz and Marcel Khalife wafting into my bedroom from the living room downstairs.

By Zena Youseph

Categories: Culture, Religion and Culture