Earlier this year, Edward Said’s daughter, Najla, published her memoir Looking for Palestine, dedicated to both her parents. In it she recounts a conversation she had with Said whilst she was at university, she writes:

“To very smart people who study a lot, Edward Said is the ‘father of postcolonial studies’ or, as he told me once when he insisted I was wasting my college education by taking a course on postmodernism and I told him he didn’t even know what it was:

‘Know what it is, Najla? I invented it!!!’

I still don’t know if he was joking or serious.”[i]

The conversation between Said and his daughter, highlights the gravitas of his work. Said’s work has influenced scholars of many, many fields – included historians, musicologists, philosophers, sociologists, anthropologists and the list goes on.

As a student of art theory, and having completed a PhD on Palestinian art and film, it will come as no surprise that Edward Said’s work has constantly been a ‘go to’ throughout my research. In fact, Said might be said to be responsible for rousing my interest in Palestinian art in my undergraduate studies. I remember the exact moment it happened – I was watching a 1988 videorecording of an interview of Edward Said by Salman Rushdie (pre-fatwa!). In the interview Said explains:

“There seems to be nothing in the world sustaining the [Palestinian] story, in other words if you stop telling it, it is just going to drop and disappear…Whereas you feel the other narratives are there and have a kind of permanent and institutional existence and you have to chip away at them.”[ii]

His words immediately resonated with an artwork I had seen called Untitled by Palestinian artist Emily Jacir (with Anton Sinkewich). The work, from 2000, involved Jacir placing a series of diverse books relating to Palestine in a niche in a gallery a wall. The books stayed suspended in the niche through – and I take poetic licence here – a solidarity of narrative. Here Jacir takes Said’s comment from the Rushdie interview and makes it an artwork. That is to say that the work literally depicts the idea that texts exist in solidarity with one another and it suggests exactly what Said had previously said – the moment you stop telling the story “it is just going to drop and disappear”.

Said’s observation that there is a need to constantly retell the Palestinian story is something I continue to encounter on every visit to Palestine. There, something as simple as asking for directions, or asking someone how long their family has owned their business has repeatedly ended in them asking me if I know what happened in 1948. And even when my reply is yes, the story is recounted regardless.

Underpinning my research as been the question of how has the collective Palestinian experience and story been recounted in art? This basic question leads to others: How has the story changed? Why is the story so difficult to tell? What are the consequences of various modes of narration? Of course, these are issues that Said takes up directly in many of his texts it is useful to look specifically at how he engages with them in an article entitled Invention, Memory and Place published in the journal Critical Inquiry in 2000.

Citing examples in the US, India, Israel and elsewhere, Said draws discussion in the article around the invention of customs and collective memories for various people around the world. He explains that the impetus behind citing these examples “is to underline to extent to which the art of memory for the modern world is both for historians as well as ordinary citizens and institutions something to be used, misused, and exploited, rather than something that sits inertly there for each person to possess and contain”.[iii]

He goes on, “people now look to refashioned memory, especially in its collective forms, to give themselves a place in the world, though…the processes of memory are frequently if not always, manipulated and intervened in for sometimes urgent purposes in the present.”[iv]

One of these urgent “purposes” Said discusses is that of Palestine. Speaking in regards to the manipulation of memory and history by the Israeli state Said writes:

“Along with the idea of Israel as liberation and independence couched in terms of a reestablishment of Jewish sovereignty went an equally basic motif, that of making the desert bloom, the inference being that Palestine was either empty (as in the Zionist slogan, “a land without people for a people without land”) or neglected by the nomads and peasants who facelessly lived on it. The main idea was not only to deny the Palestinians a historical presence but also to imply that they were not a people who had a long-standing peoplehood.” [v]

It is in this section of the article that things get both much heated and revealing. Said writes:

“As late as 1984 a book by a relative unknown called Joan Peters appeared from a major commercial publishing house (Harper and Row) purporting to show that the Palestinians as a people were an ideological, propagandistic fiction; her book From Time Immemorial won all sorts of prizes and accolades from well-known personalities like Saul Bellow and Barbara Tuchman, who admired Peters’s ‘success’ in proving that Palestinians were ‘a fairy tale’. Slowly, however, the book lost credibility despite its eight or nine printings, as various critics, Norman Finkelstein principal among them, methodically revealed that the book was a patchwork of lies, distortions, and fabrications, amounting to colossal fraud. The book’s brief currency (it has since practically disappeared and is no longer cited) is an indication of how overwhelmingly the Zionist memory had succeeded in emptying Palestine of its inhabitants and history, turning its landscape instead into an empty space…”[vi]

I can admit that when I first read the following passage I was moved to tears. Said writes:

“I remember my rage at reading a book that had the effrontery to tell me that my house and birth in Jerusalem in 1935 (before Peters’s flood of ‘Arab’ refugees) to say nothing of the actual existence of my parents, uncles, aunts, grandparents, and my entire extended family in Palestine were in fact not there, had not lived there for generations, had therefore no title to the specific landscape of orange and olive groves that I remembered from my earliest glimmerings of consciousness. I recall also that in 1986 I purposefully published a book of photographs by Jean Mohr, After the Last Sky: Palestinian Lives for which I wrote an elaborate text whose effect with the inter-connected pictures I hoped would be to dispel the myth of an empty landscape and an anonymous, nonexistent people.”[vii]

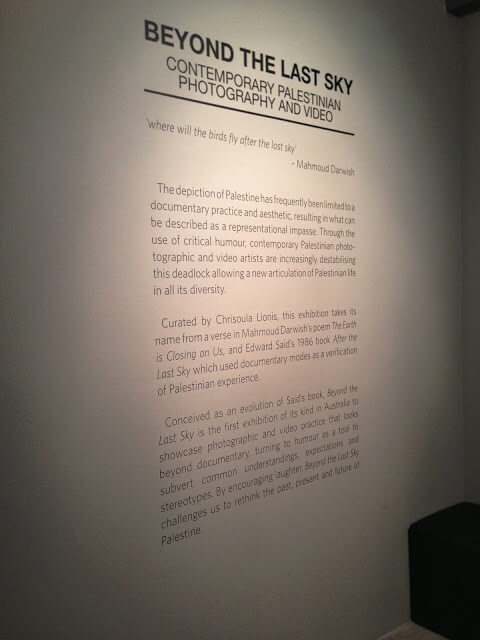

I carried this passage with me for many years, before and during the writing of my PhD. When the opportunity came up to curate an exhibition that came from my research on humour in Palestinian art, I decided to draw a direct reference to Said’s 1986 text. The exhibition at the Australian Centre for Photography last year was entitled Beyond the Last Sky. Of course the title Beyond the Last Sky was not only a reference to Said’s text but was also a reference to Mahmoud Darwish’s poem The Earth is Closing on Us where Darwish writes the now famous lines – “Where can we go on crossing this last border? Where do the birds fly after the last sky? Where do plants sleep when all winds have passed?”

Darwish’s poem was a reflection on the repeated Palestinian experience of exile. What interested me was that Edward Said chose to reflect upon the Palestinian experience of exile via the medium of photography. More significantly he was looking to actively refute claims (specifically those of Joan Peters) that Palestinians did not exist using documentary photography as a tool of political, cultural and historical validation.

When curating the Beyond the Last Sky exhibition, I asked myself what role does Palestinian photographic practice have today almost three decades after Said’s text was published. The exhibition at the Australian Centre for Photography was curated as though it was an evolution of Said’s book and this was the reason behind the deliberate addition of the word ‘beyond’ in the exhibition’s title. The inclusion of the word ‘beyond’ was for two reasons. Firstly, it was an acknowledgement that it would seem the myth so long propagated that Palestinians were an anonymous non-existent group has now, at least for people with any sense whatsoever, been debunked. Secondly, the show also consciously looked beyond documentary modes and aesthetic that have so long characterised and dominated the representation of Palestine.

The basis of the exhibition and indeed my PhD research was to seek to prove how tactics of humour employed by Palestinian artists function as an alternative way of telling the Palestinian story. Again here again Said’s influence is apparent. An investigation of humour is in line with some of Said’s most important teachings; in that it can challenge us to understand the construction of history, to take stock of our assumptions, prejudice and stereotypes and it can reframe the boundaries of identification with people, places and identities.

Let me conclude by saying this: my work owes a lot to Edward Said. I, as, a person moving through the world owe a lot to Said. Artists, activists, students and academics around the world owe a lot to Said. I am honoured to be given the opportunity to publicly remember this trailblazer, who reminded us to question history and culture and he reminded us of why it is necessary to always ‘speak truth to power’.

References:

[i] Najla Said, Looking for Palestine: Growing up confused in an Arab-American family (New York: River Head Books, 2013) 4-5.

[ii] Edward Said in Edward Said with Salman Rushdie, videorecording, ICA Video, 1986

[iii] Edward Said, ‘Invention, Memory, and Place,’ Critical Inquiry, 26.2 (2000) 179.

[iv] ibid.

[v]Edward Said, ‘Invention, Memory, and Place,’ 187.

[vi]Edward Said, ‘Invention, Memory, and Place,’ 187 – 188.

[vii]Edward Said, ‘Invention, Memory, and Place,’ 188.

Chrisoula Lionis

Researcher and curator at the National Institute for Experimental Arts.

Categories: Religion and Culture